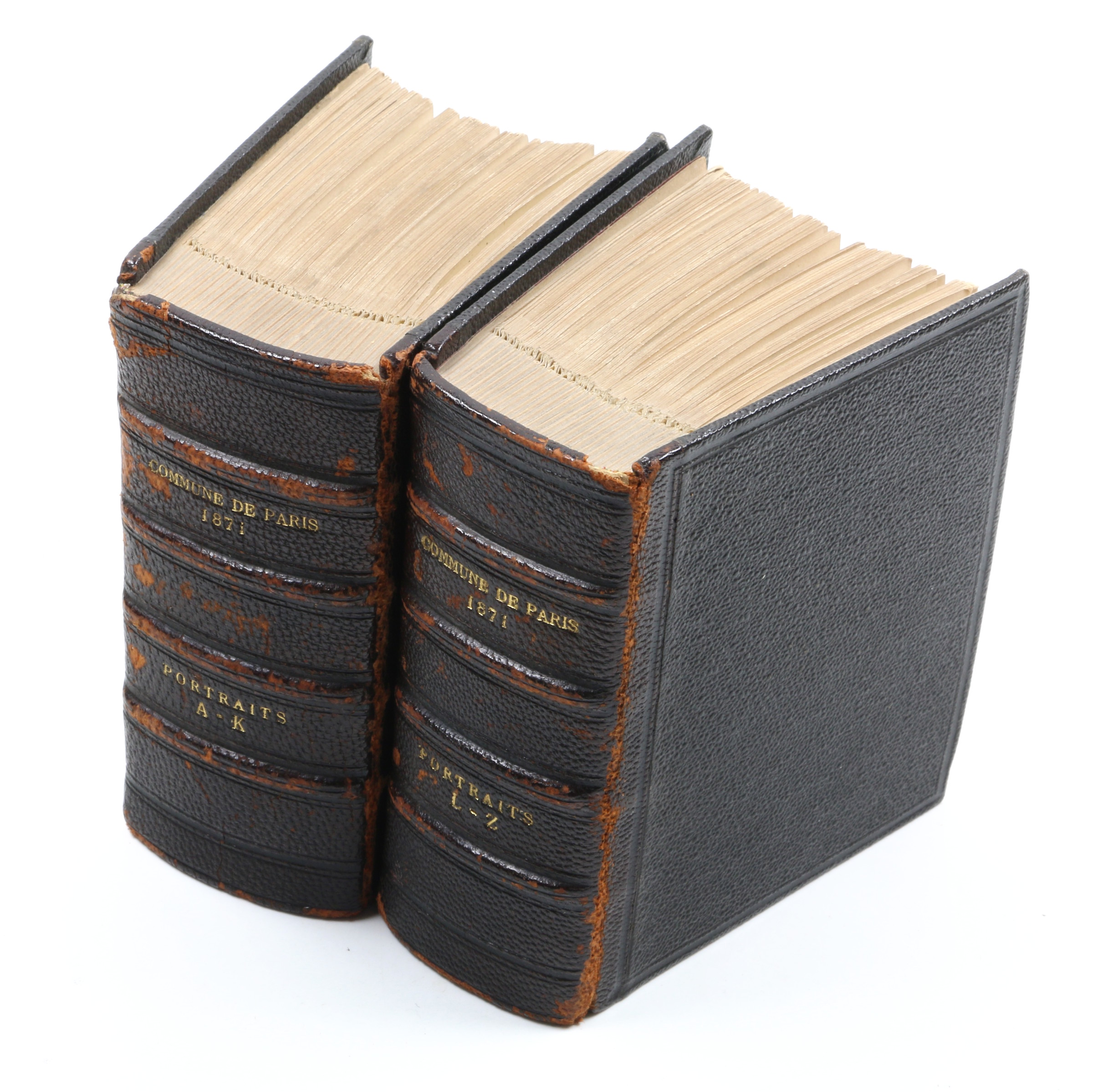

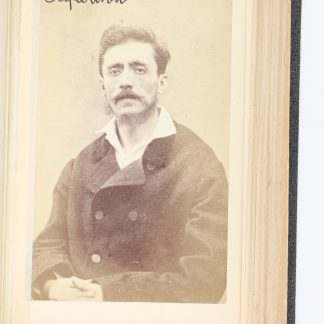

119 Annotated Portraits of Communards, From the Library of the Chief of Police

Photo album of wanted Communards for the use of French police detectives.

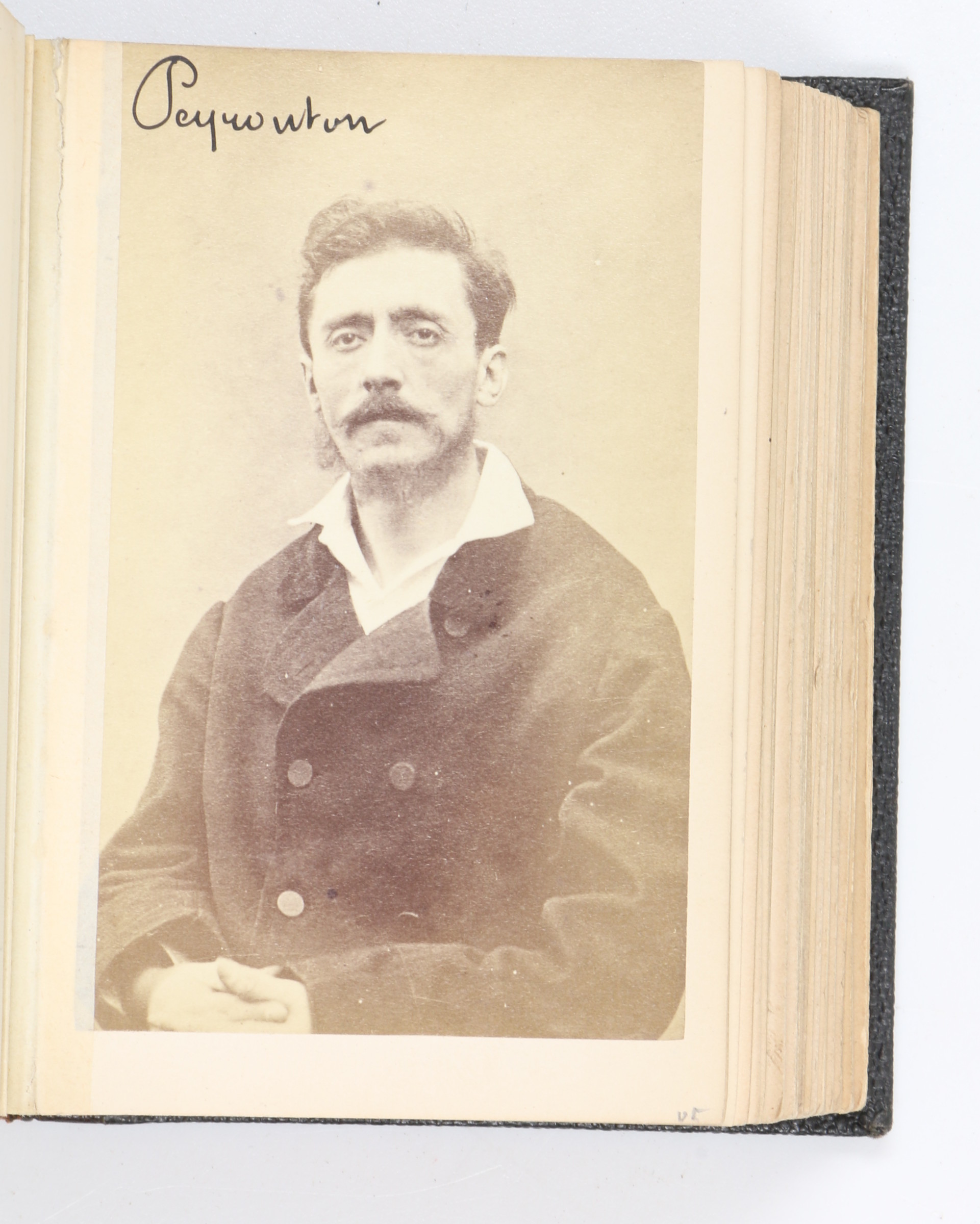

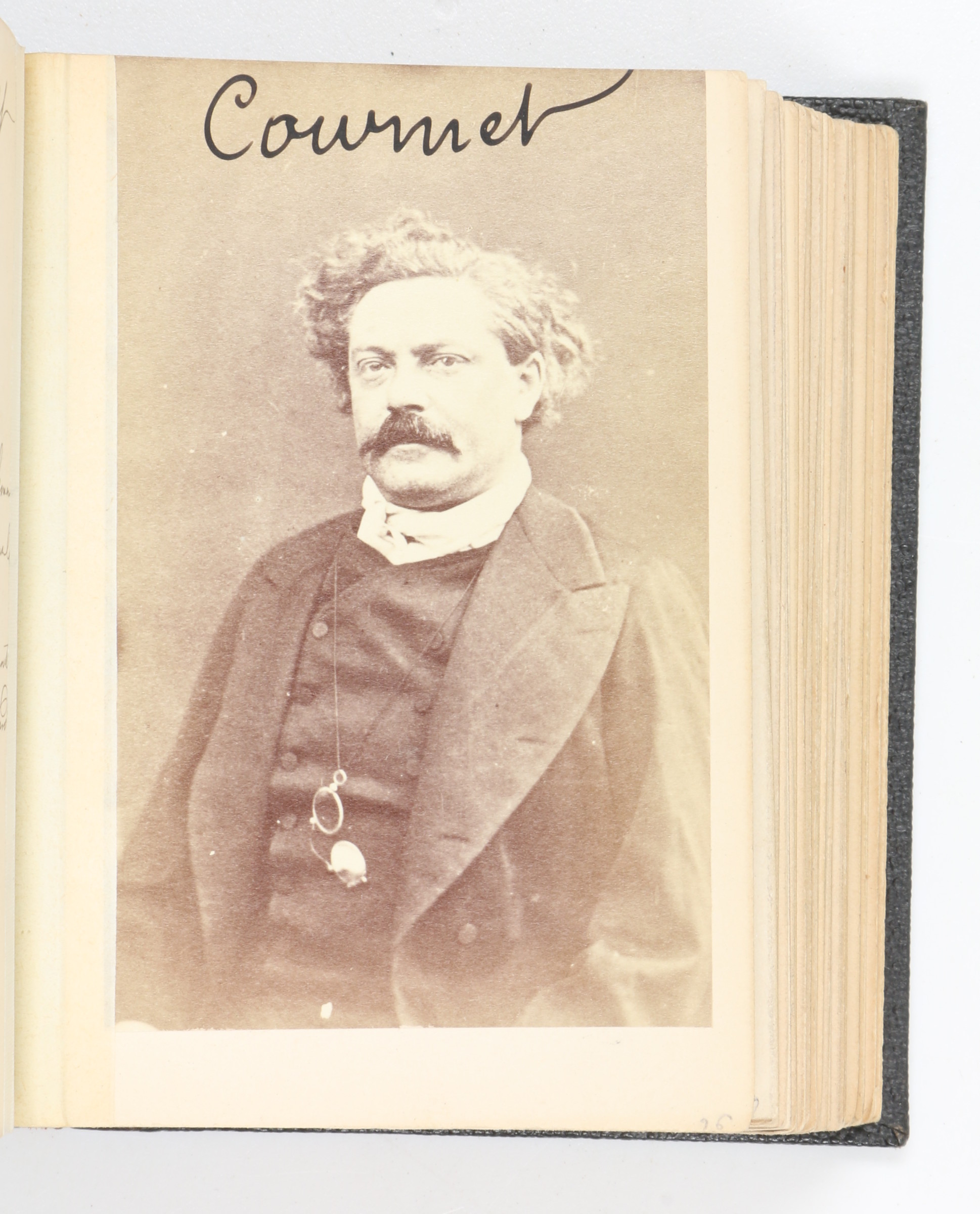

A total of 119 photographic portraits of 74 Communards, captioned in black ink by police officers. 63 & 56 photographs mounted on tabs and assembled in alphabetical order, bound in 2 contemporary half calf 12mo volumes on four raised bands with gilt titles to spines. Portraits are mainly by the photographer Ernest Appert (1830-90) and captioned on front, reverse, or both.

€ 75,000.00

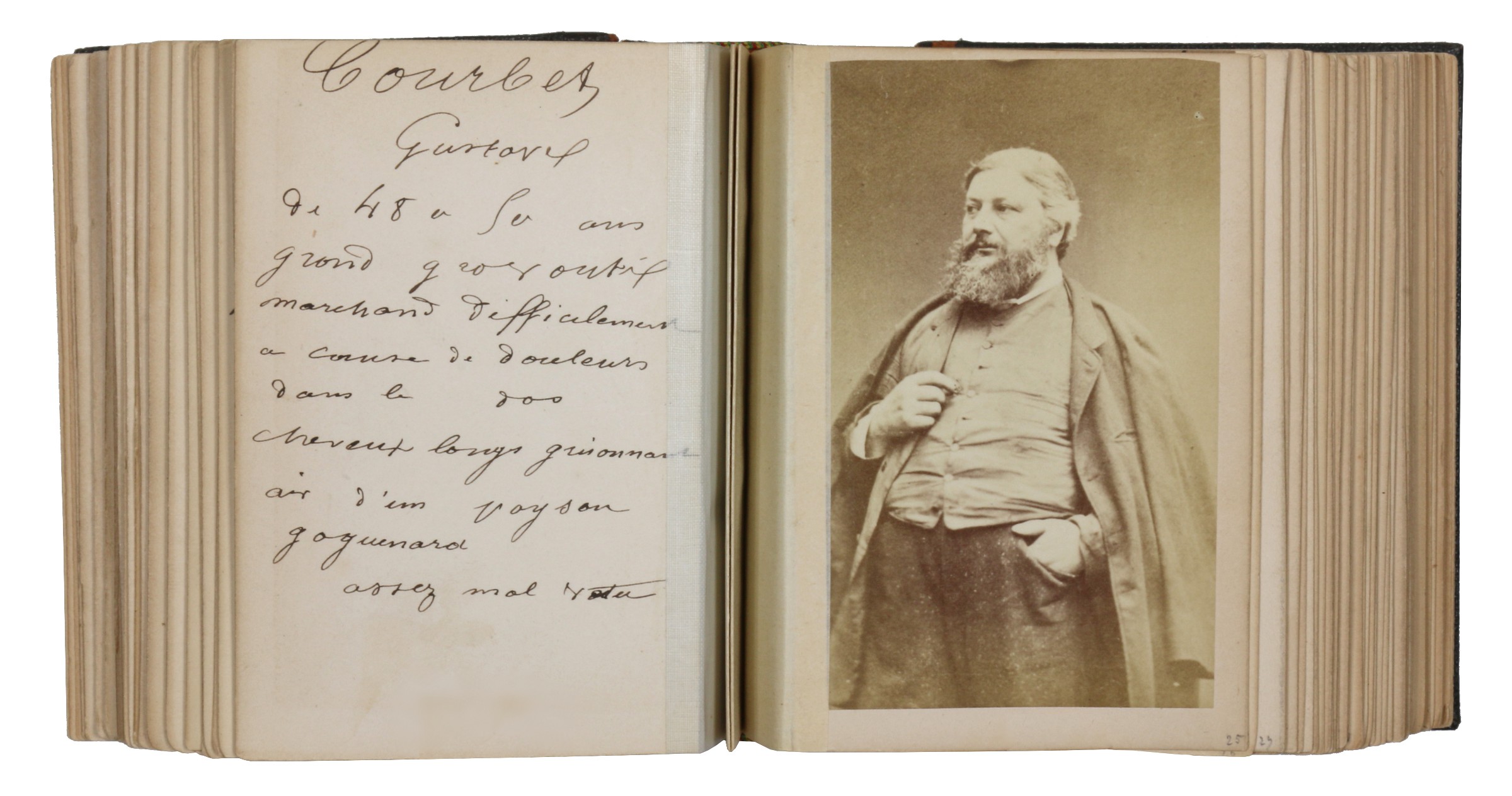

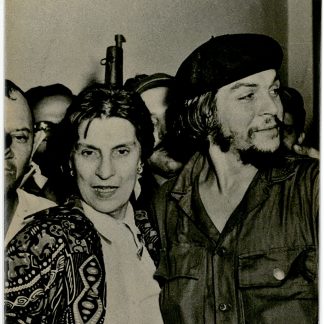

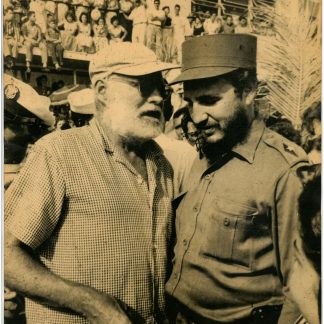

An exceptional pocket-sized rogues' gallery showing Communards, for the use of Parisian police detectives on the manhunt, from the estate of Edmond Louis de Nervaux, director of the Sûreté générale at the French Ministry of the Interior from 1871 to 1874. Among the many great and lesser men here portrayed for their involvement in the uprising are Bakunin, "chef de l'Internationale", Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, later the historian of the Commune and sometime fiancé of Marx's daughter Eleanor (Tussy) Marx, the painter Gustave Courbet ("grand, gros, voûté, marchant difficilement à cause de douleurs dans le dos, cheveux longs grisonnants, air d'un paysan goguenard, assez mal vêtu"), Henri Rochefort ("taille élevée, cheveux noirs frisés, barbe noire, teint pâle, traces de variole"), and Jules Vallès ("taille un peu au-dessus de la moyenne, barbe et cheveux noirs à reflets rouges, teint légèrement basané, peau un peu ridée, marche assez lourdement"). The formulaic description of face, hair, eyes etc. entirely mirrors the usage that was common even under the Ancien Régime and that was given full expression in the prisoner lists compiled during the mass incarcerations under the French Revolution's "Terreur". The more colourful (and frequently unflattering) annotations, however, reflect an increasing demand for a greater degree of individual detail that would eventually lead to Bertillon's anthropometric system of physical measurements. In the present albums, many of these notes amount to rather picturesque nutshell psychological sketches: "air quelque peu ahuri" (Albert Breuillé), "figure fatiguée" (Jean-Baptiste Édouard Millière), "air souffrant" (Tony Moilin), "figure très commune, nez un peu chafouin" (Trabucco), "cheveux et barbe blond filasse, air fiévreux, yeux malins légèrement bordés de rouge, porte plus souvent un pince-nez en argent que des lunettes" (Marc Amédée Gromier), "air très militaire" (Jaroslaw Dombrowski), "se tient très droit, tournure prétentieuse" (Gustave Maroteau), "vêtu généralement d'habits bourgeois, coiffé d'un chapeau de feutre mou brun" (Gustave Paul Cluseret), or "habituellement coiffé d'un chapeau tyrolien, un peu voûté" (Ferdinand Gambond).

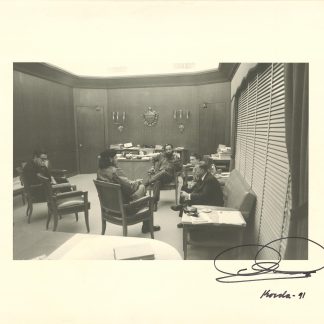

Some pictures are in duplicate or even in triplicate, with the same annotations on the back, though often by another hand, and some Communards are the subject of several different portraits. Although three photographs are on the studio cardboard of E. Flamant and F. Clement, and one (that of Auguste Rogeard) is even reproduced from a publication, the vast majority - though unsigned - apparently are the work of Ernest Appert, a prominent Parisian photographer who long had portrayed in his studio the conservative élite and republican-minded politicians alike. As Sotteau Soualle demonstrated in her 2010 dissertation on Appert, the artist began to cultivate a close relationship with the French police and judiciary in 1870, after the failed January uprising. These contacts allowed him now to photograph the accused revolutionaries and members of the International, as well as their defense lawyers, and thus to assemble an even more encompassing portrait gallery of the French political world. There is little formal difference between Appert's studio and court sittings: even in the 1860s, Appert had developed his definitive, reduced style, consisting of a half-length portrait against a blank background - a design that was easily reproduced outside the studio and even in jails with the use of a chair and a white sheet of cloth (also, the resulting images lent themselves well to photomontage, another specialty of Appert's). Many of the insurgents, put on trial in July 1870 and later released, came to play important roles in the Commune of 1871; other prominent Communards without a police record nevertheless had had their portraits taken by Appert in earlier years. Hence, when the National Assembly cracked down on the Commune, they had a wealth of negatives in the photographer's archives on which to draw for compiling their lists of wanted men. The pocket-sized volumes were clearly intended to be carried by police detectives in the field, the duplicates ensuring that a portrait could always be handed out to an informer, if necessary. Appert's well-known portrait of Louis Auguste Blanqui is not present, as the man whom Marx identified as the leader the Commune lacked was already in jail (where he would stay until 1879). On the other hand, the police was on the lookout for Bakunin, who in fact was hiding in Switzerland and did not participate in the Commune.

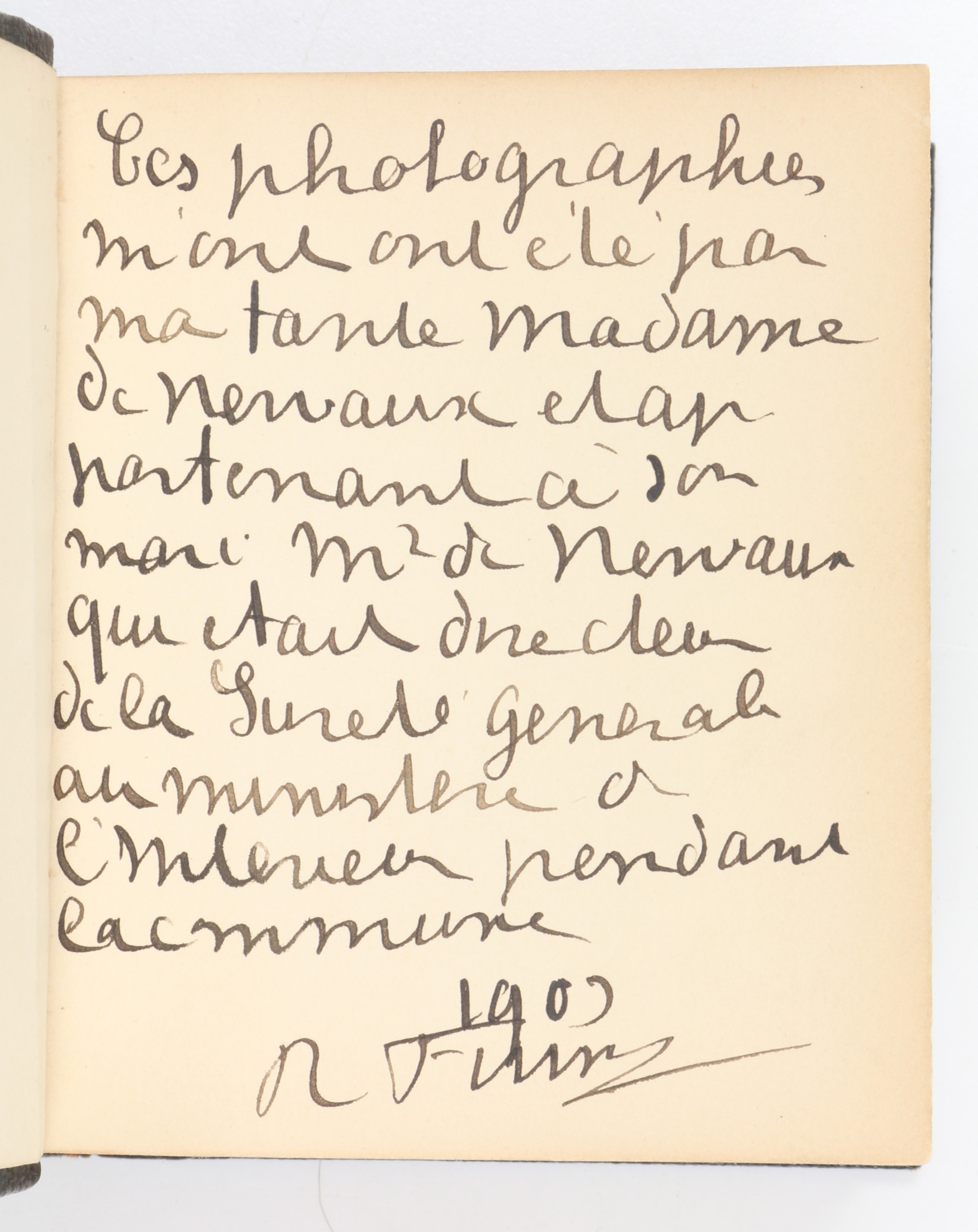

Spines very lightly rubbed, but an extremely attractive, unique ensemble. A provenance note on the flyleaf, dated 1909, states that the owner inherited the set from his aunt, the widow of Edmond de Nervaux, a high-ranking police officer during the uprising who rose to Chief of Police in November 1871.

Cf. Stéphanie Sotteau Soualle, "Ernest Appert (1831-1890), un précurseur d'Alphonse Bertillon en matière de photographie judiciaire?", in: Pierre Piazza, Aux origines de la police scientifique (Paris, 2011), pp. 54-69.