1522 travel and navigation advice by Ferdinand Columbus for Emperor Charles V, the knowledge most likely taken from his experience accompanying his father in his Fourth Voyage to America in 1502

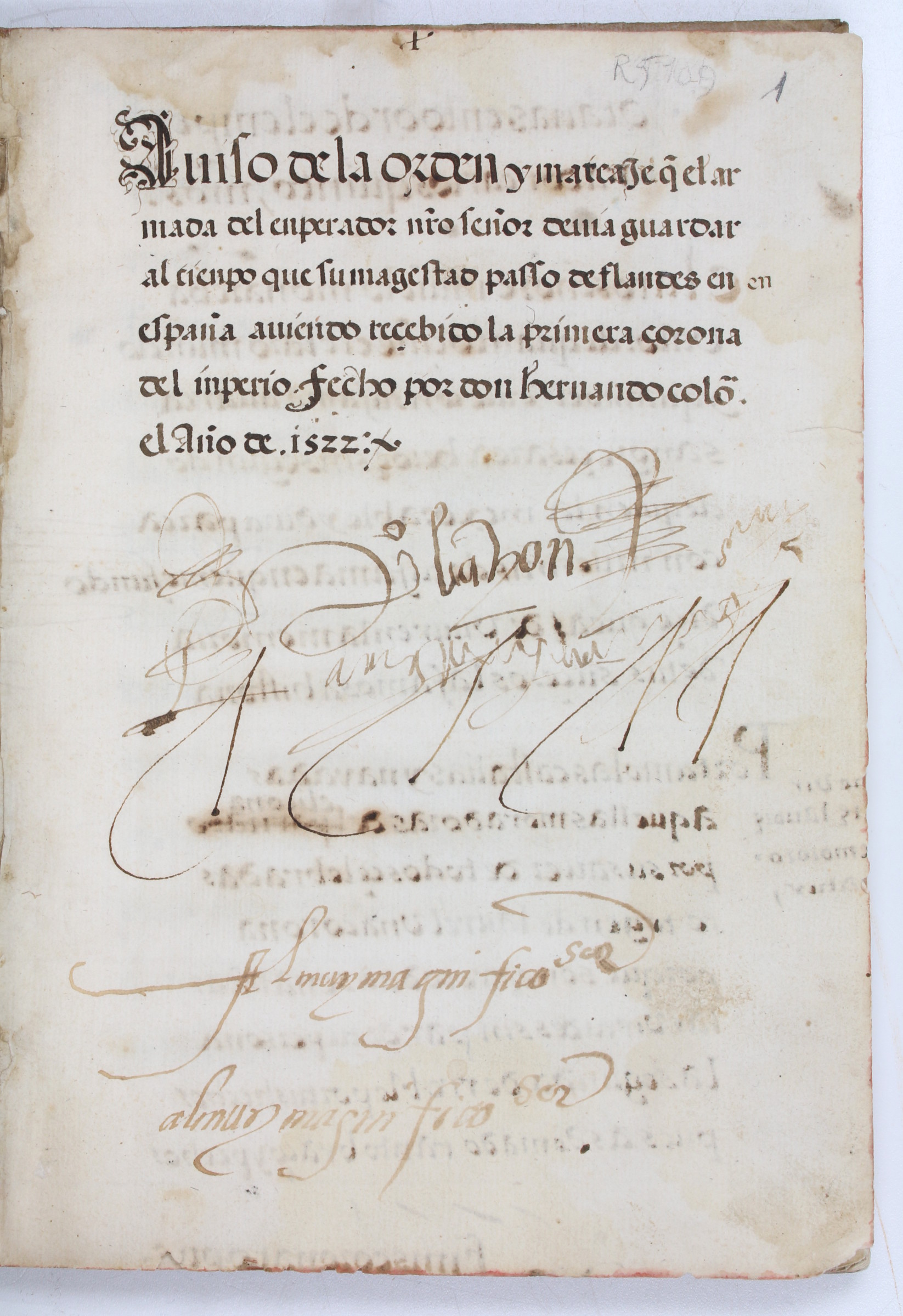

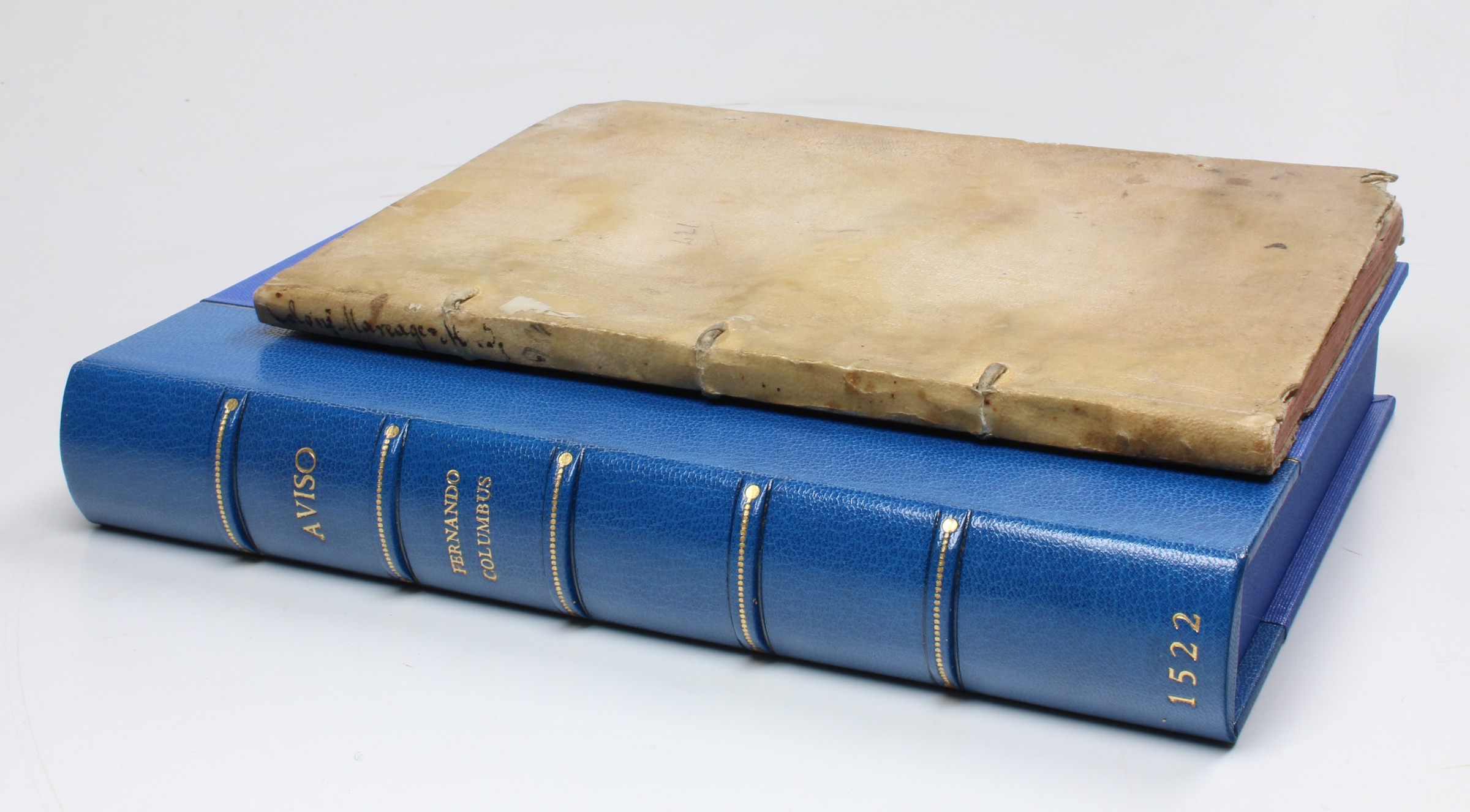

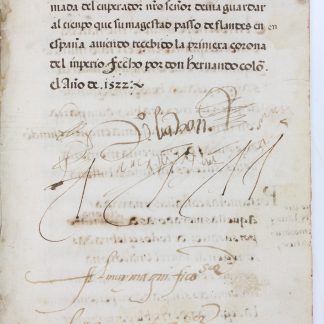

Aviso de la Orden y Mareaje a la Armada del Emperador Nro Señor Debia Guardar al Tiempo que su Majestad Paso de Flandes en España Habiendo Recibido la Primera Corona del Imperio Fecho 1522.

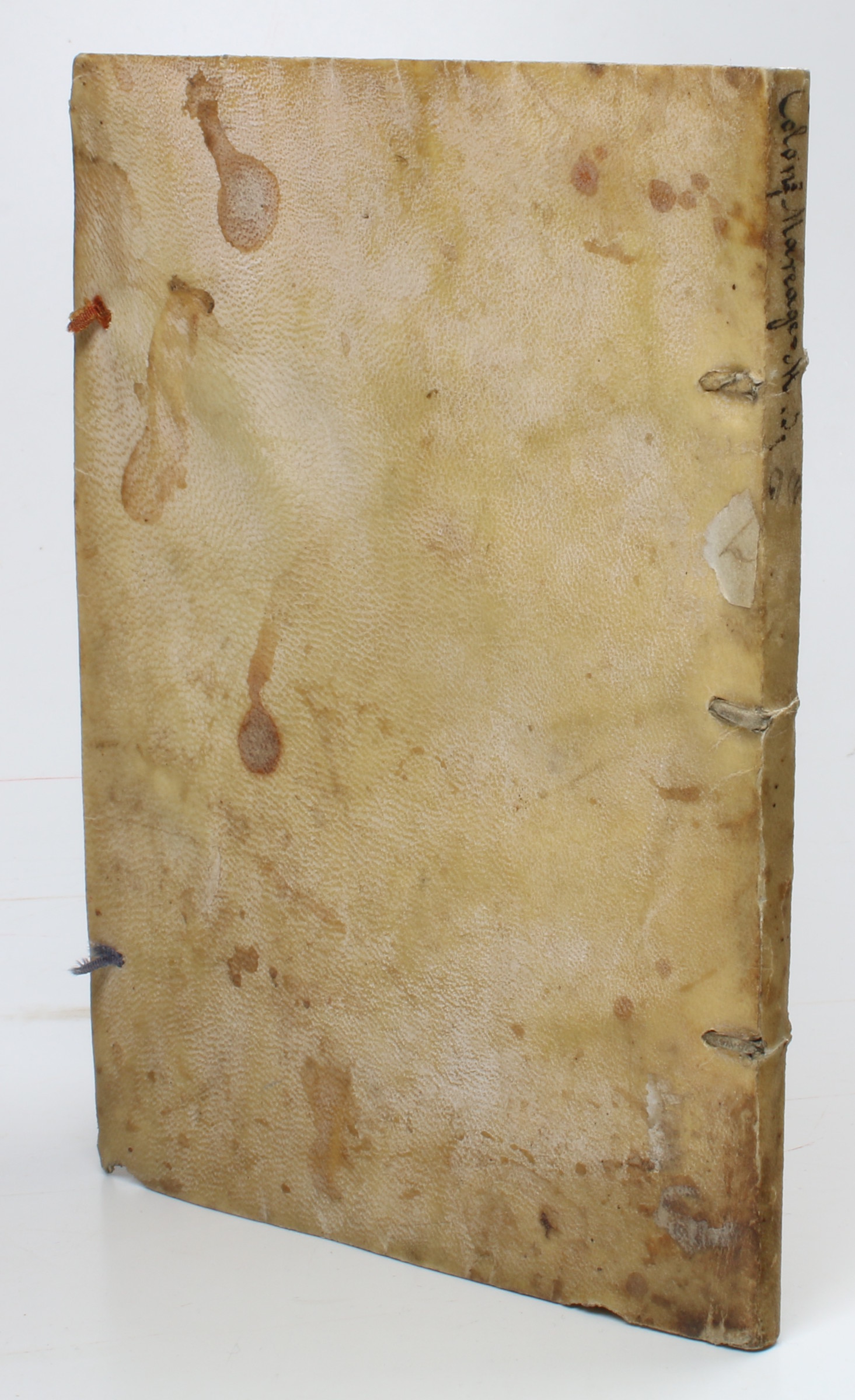

4to. 79 pp. Contemporary manuscript. Paper watermarked with hand and star motif (Briquet, Les Filigranes 10772) dating it to ca. 1507 and from Konstanz, to the southwest of Worms. Contemporary limp vellum with remains of ribbon ties; reddened edges. Stored in custom-made blue half morocco solander box with gilt spine.

€ 250,000.00

Exceptional manuscript by Hernando Colón (Fernando Columbus), one of the first people to travel to America as early as 1502, and son of the most famous explorer of all times.

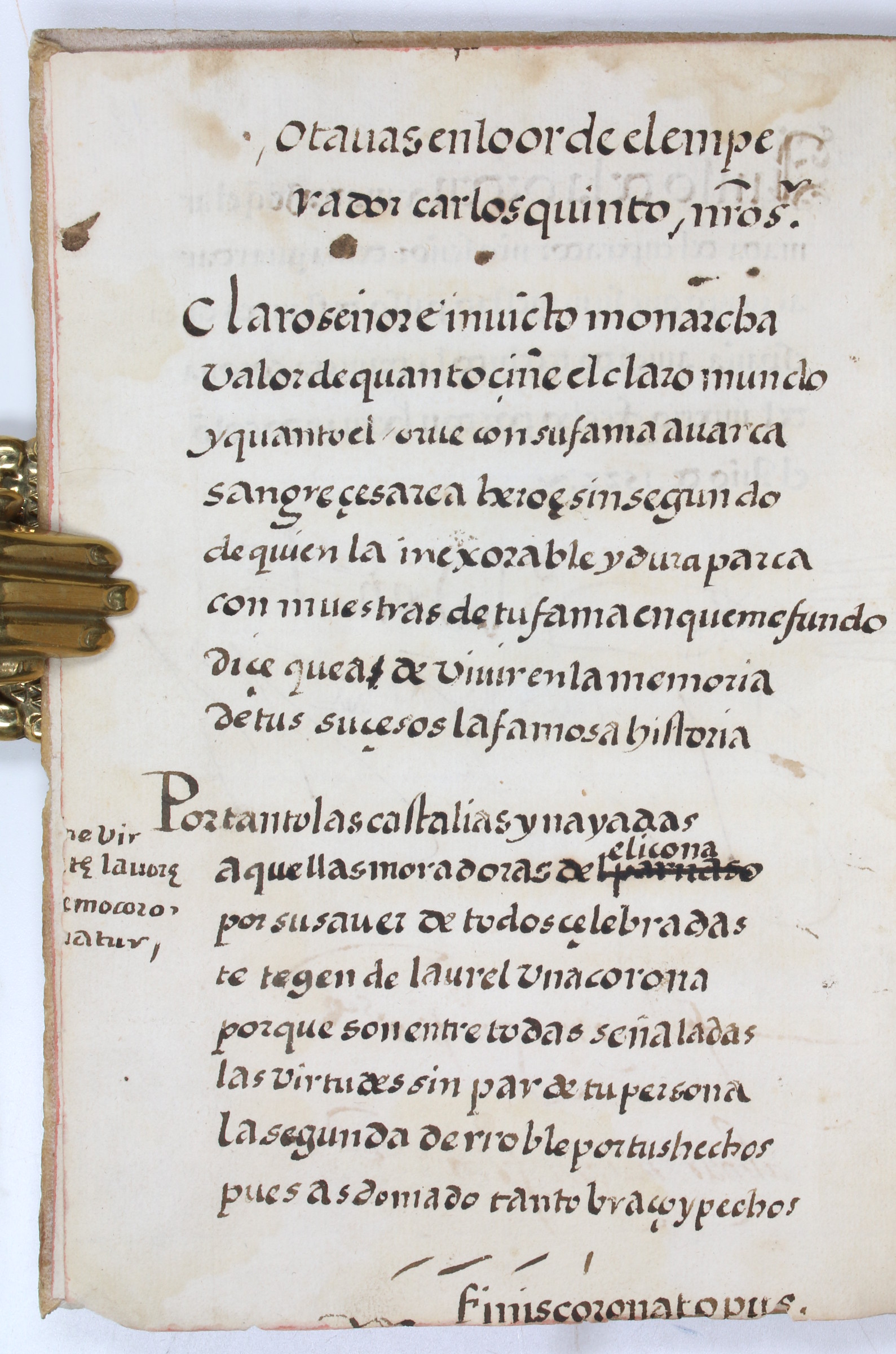

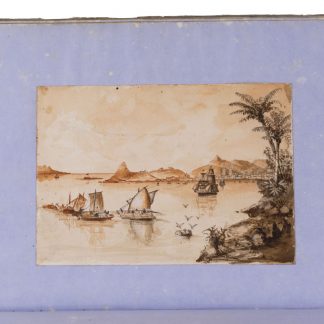

The present "Aviso de la Orden y Mareaje" was composed by Hernan Colón (1488-1539), one of the first Europeans to travel and explore the coasts of America, a renowned bibliophile and the son of Christopher Columbus, to provide the recently crowned Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, with a set of guidelines for travelling by sea from Flanders to Spain in 1522. Hernando Colón formed part of Charles’s retinue and accompanied him on this 1522 voyage. He based his advice on his own extensive knowledge of sea travel that dated from his sailing as a 13-year-old boy on Christopher Columbus's fourth and most dangerous voyage to the Americas (1502-04) when father and son, in the course of exploring the American mainland coast between Honduras and Panama, had been shipwrecked on Jamaica for almost a full year.

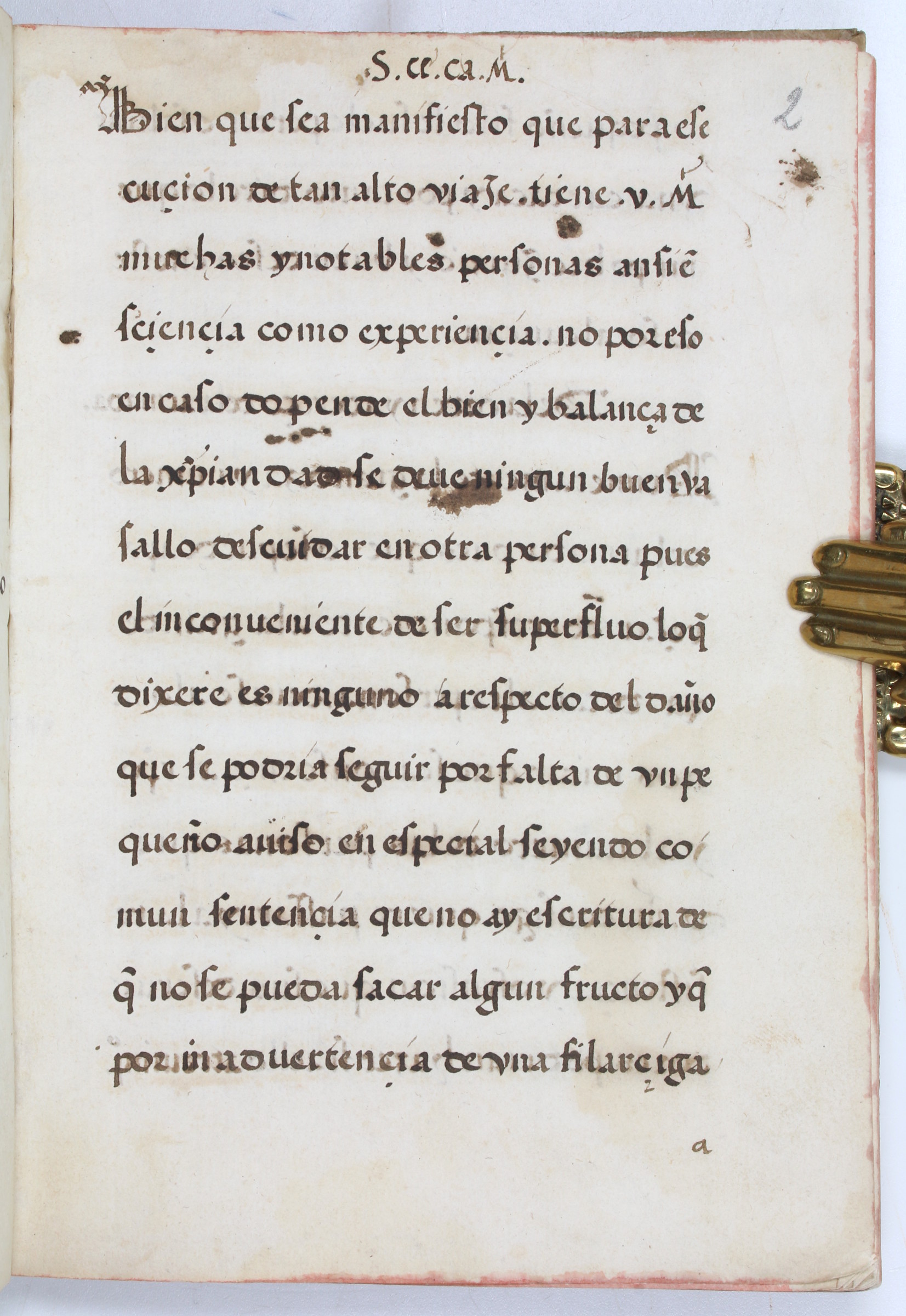

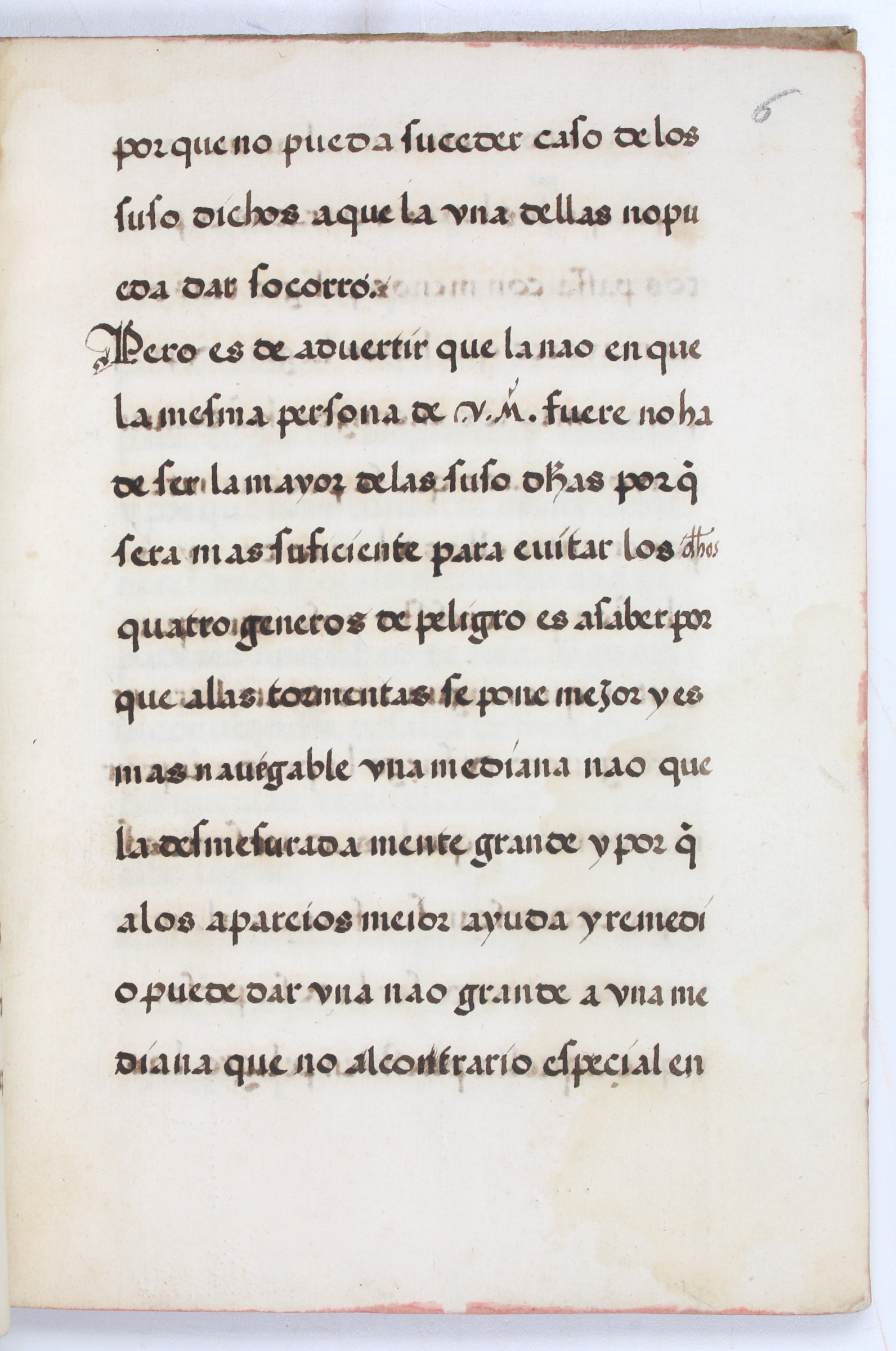

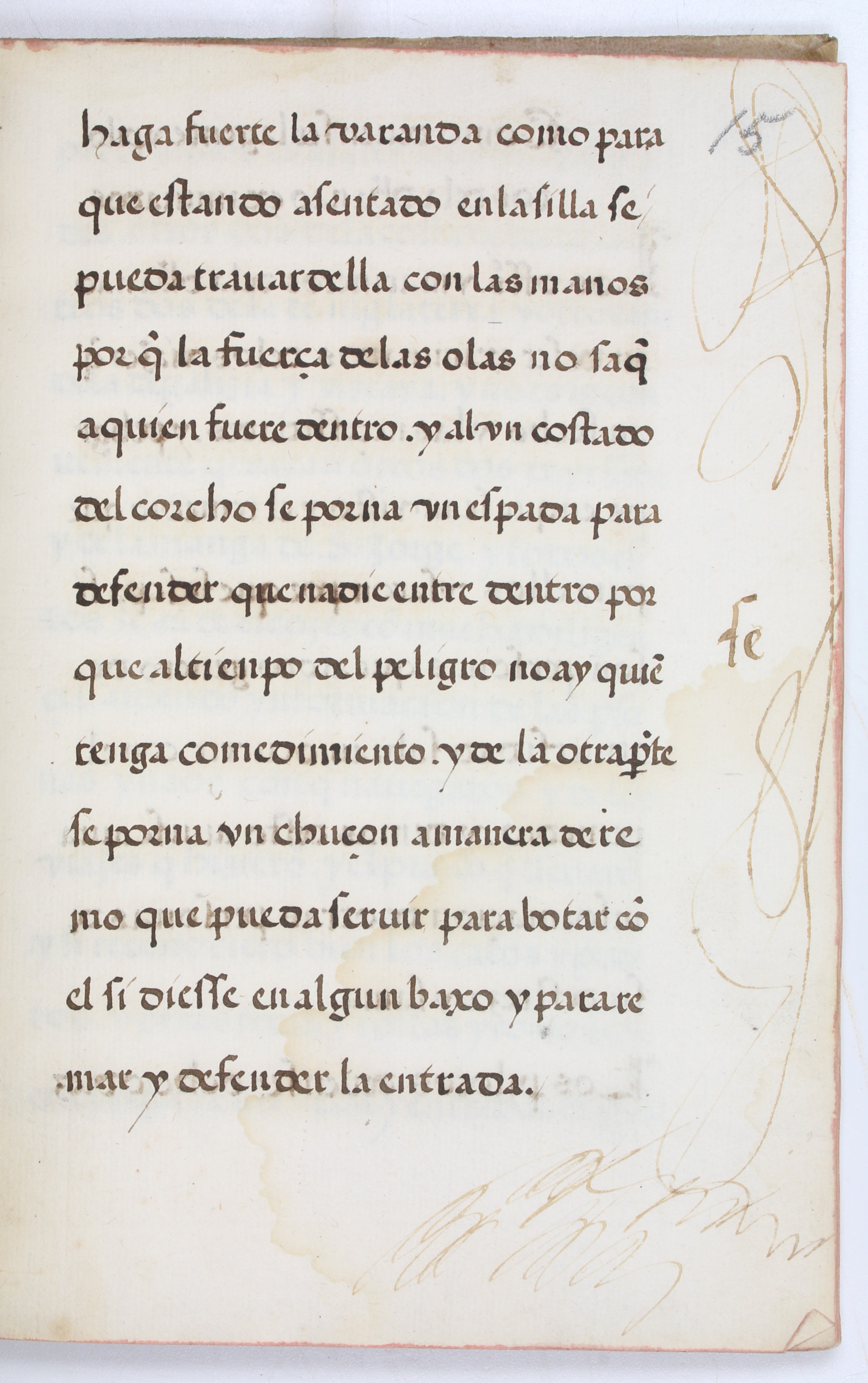

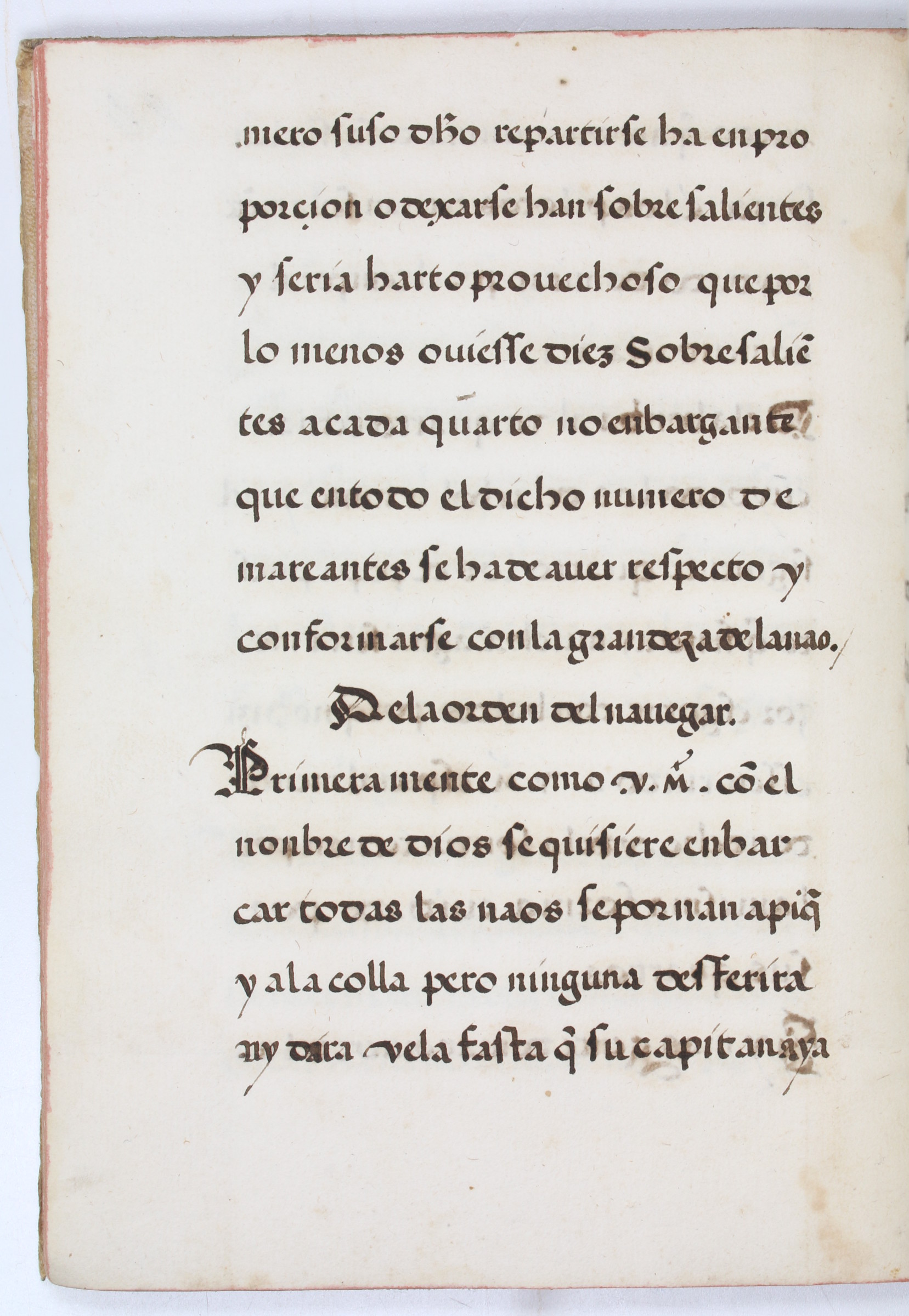

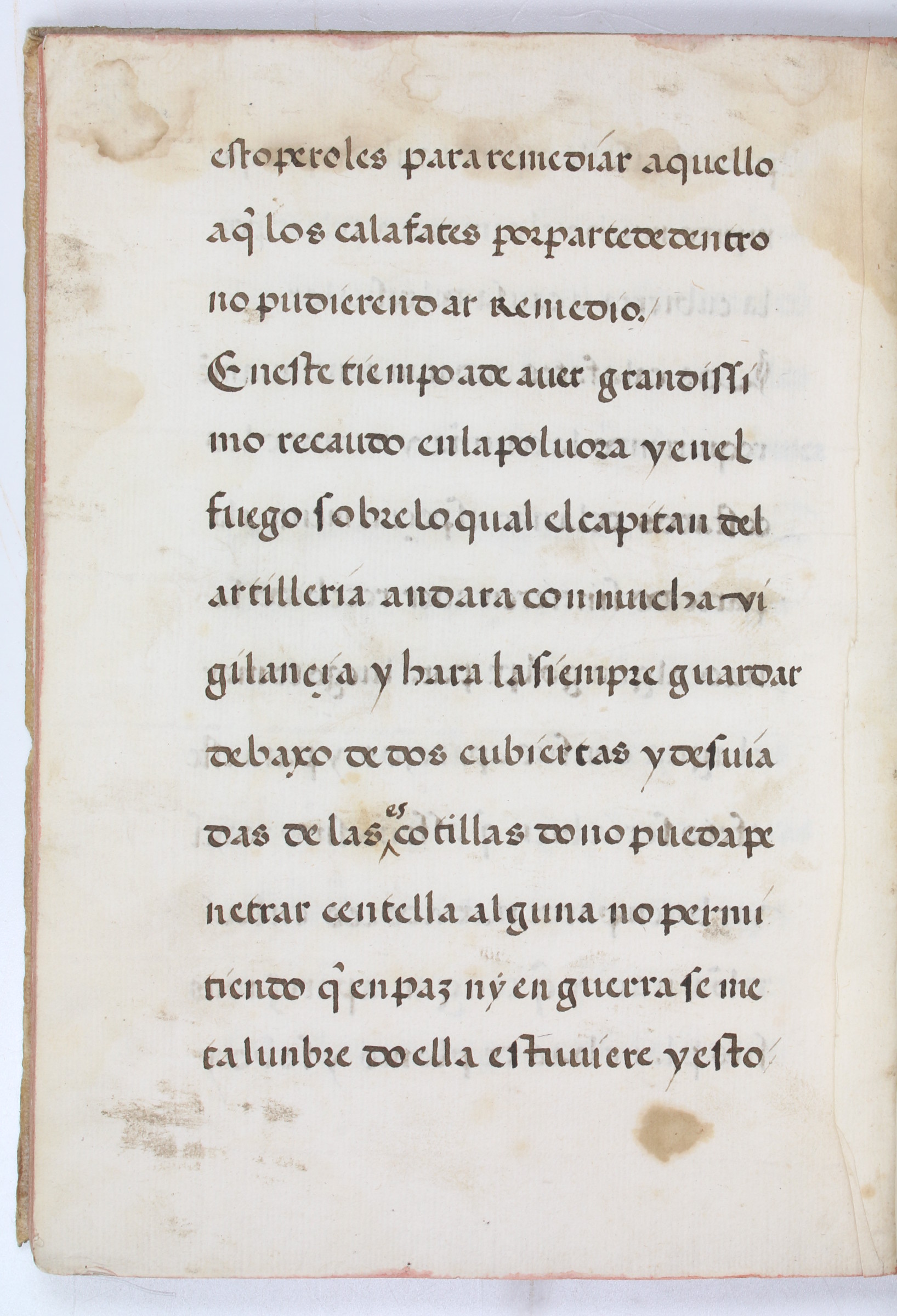

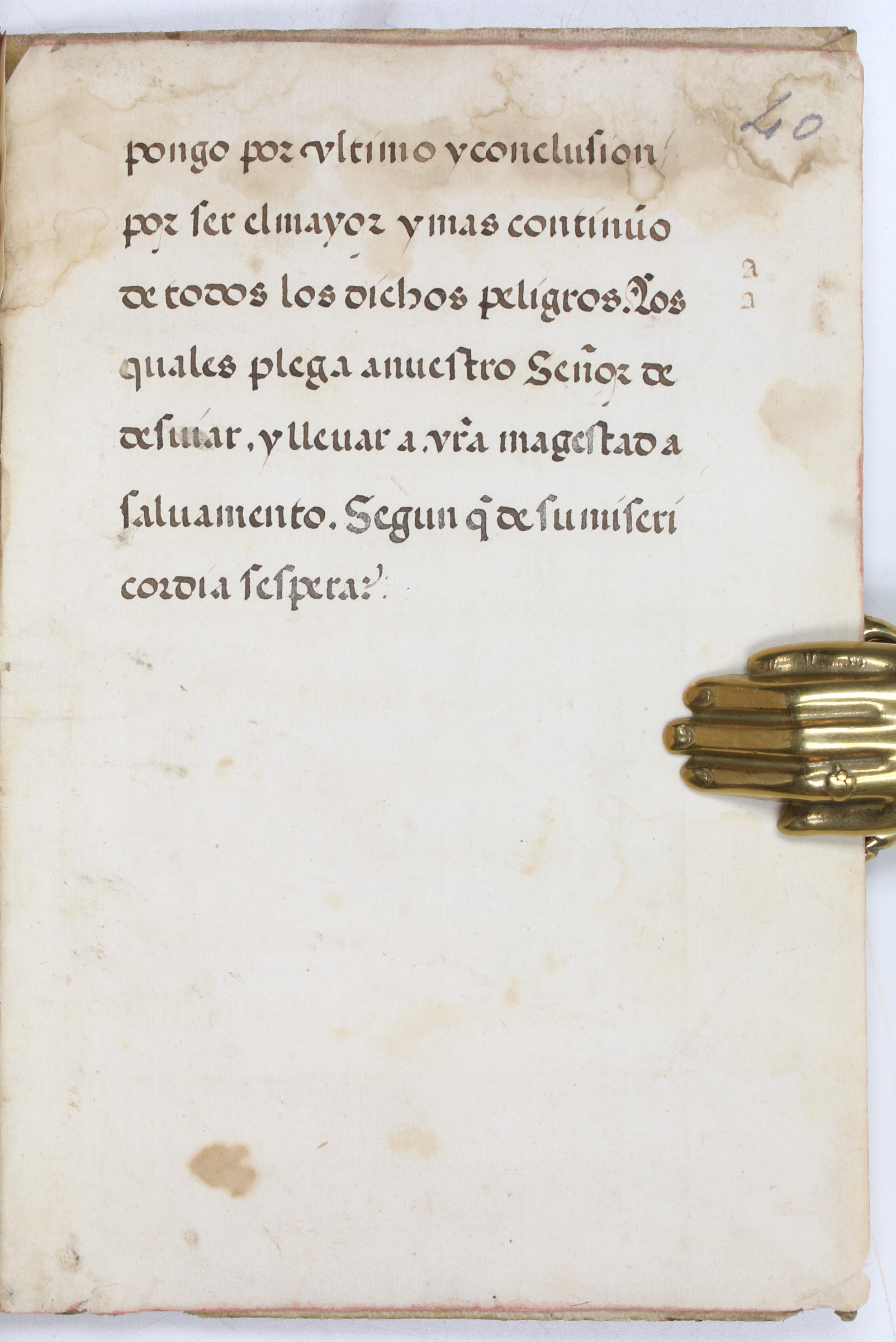

In this treatise, Hernando, who had been a member of the Spanish royal court from a young age, is surprisingly frank with Charles V about the practical measures he recommends for a safe journey. He notes that the dangers at sea "usually come from one of four reasons. The first is due to too much tempest. The second, lack of some necessary rigging [in this context, probably equipment]. The third, due to shoals, banks and reefs. The last, as a result of the opposition of enemies" ("suelen venir por una de quatro causas. La pr[i]mera por demasiada tormenta. La segu[n]da por falta de algun aparejo. La tercera por razon d[e] baxos y bancos y arracifes. La ultima por contrariedad d[e] enemigos", ff. 5v-6). Hernando then proceeds to explain the measures by which these dangers can best be offset, thereby discussing the numbers, types and sizes of ships which should compose the emperor's fleet; the manner in which each of these vessels is to be selected and inspected to ensure their seaworthiness; and the way in which each of these was to be fitted out, armed, manned and governed.

Hernando's advice is comprehensive when it comes to the organization of such a journey but even extends to the management of the emperor himself, including details of where on the "nao" Charles should have his quarters, his daily routine, the number of attendants he should have, and even on what he should eat. Here, Hernando notes that "it is also commonly held that anything sour, for being cold, is harmful, for which reason it is considered better to have meals such as stews, not phlegm-inducing foods, and warm preserves such as nutmegs and ginger, as well as good, sweet-smelling wines and those seasoned with spices such as hippocras or spiced white wine. Fruits, cheese and onions should be avoided. Above all, one should be well wrapped up, especially the stomach and the feet, and one should not occupy the mind with business or writing but only in leisure, going out to take fresh air regularly without looking too much at the sea. Some consider it very welcome to purge oneself lightly even before going on board and eating during the first days with some moderation" ("Tanbien [!] es comun opinion qu[e] toda cosa agria por ser fria es nociva por lo qual tienen por meior manjares exutos y asados y no flemosos y conservas calientes y oderiferas como nuezes moscadas y gengibre y buenos vinos odoriferos y algunos dellos adobados con especicas [!] como el hypocras, y la clarea, y devêse evitar las frutas, y el q[ue]so y las cebollas y sobre todo andar bien arropado especialmente el estomago y los pies y no ocupar el sentido mucho en negocios ni escrituras salvo en tomar plazer y salir do corte el ayre fresco sin mirar mucho la mar y aun algunos a[n]te del enbarcar [!] hallan muy saludable purgarse ligeramente comiendo los primeros dias con alguna regla", ff. 11v-12).

Despite its value for the history of travel and for an understanding of 16th century approaches to the transport by sea of high-status individuals such as Charles V, the "Aviso de la Orden y Mareaje" remains apparently unpublished and little known, most likely because it was written so relatively early in Hernando Columbus's career and due to the extreme rarity of surviving copies. Scholars have been aware of the Aviso’s existence in part through a reference to it made by Columbus himself in 1524 in the "Declaracion del derecho que la Real corona de Castilla tiene …", where he noted that "I ventured to write to Your Majesty with that Treatise or order of navigation for the most high and happiest voyage of the Emperor, from Flanders to Spain" ("me atreví a escribir a V.M. con aquella Escritura o forma de navegación para el alto y felicísimo Viaje del Emperador, desde Flandes en España"; original version available online from the Real Biblioteca, II/652, and published in M. Salvá & P. Saínz de Baranda, Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España, Madrid: La Viuda de Calero, 1850, XVI, document 3, pp. 382-420, at p. 383).

Juan Guillén Torralba has noted that "among the papers that Don Hernando kept until the end of his days and which were referred to by his executors, there appeared one that, almost certainly, is that of the voyage of Charles V, which has as a title: Aviso de la orden y mareaje … del Emperador" ("Entre los papeles que conservó don Hernando hasta el final de susdías y de los que hicieron relación sus albaceas, apareció uno que, casi seguro , es este del viaje de Carlos V, que lleva como título: Aviso de la orden y mareaje ... del Emperador", Guillén Torralba, Hernando Colón: humanismo y bibliofilia, Seville: Fundación José Manuel Lara, 2004, p. 101). It was included, as Torralba suggests, in an inventory of Columbus's writings found in his possession at the time of his death in 1539 ("Inventario de Escrituras", Archivo Histórico de Protocolos de Sevilla, Oficio V. Escribania de Pedro de Castellanos. Legajo 6. de 1539. Carpeta especial. Folio I, possibly printed in A. Muro Orejón and J. Hernández Díaz, El Testamento de Don Hernando Colón y Otros Documentos para su Biografía, 1941), though there is now no record of it in what remains of Hernando’s library, the Biblioteca Colombina in Seville. A further copy, described in 1593 as "Avisso de la orden que devía guardar la armada del enperador, nuestro señor, al tiempo que su Magestad passó de Flandes en Spaña", was recorded in an "Ynbentario de la librería del marqués Don Alonso Ossorio" (see Pedro M. Cátedra, Nobleza y Lectura en Tiempos de Felipe II: La biblioteca de Don Alonso Osorio Marqués de Astorga, Madrid: Junta de Castilla y León, 2002, p. 503, no. B679). Cátedra notes that the text of the manuscript in the Marqués de Astorga’s collection matched the copy of the "Aviso de la Orden y mareage que el Armada del Emperado debia guardar al tiempo que su majestad pasó de Flandes en España habiendo recibido la corona del Imperio. 1522" sold in the Catálogo de … Gabriel Sánchez, 31, which Marín Martinez et al. (Catálogo concordado de la biblioteca de Hernando Colón, Madrid: Fundación Mapfre, 1993, I, 265f.) describe as lost. Whether this is the same copy as the present manuscript is uncertain, though no mention is made by Cátedra of the manuscript having belonged to the Spanish statesman and bibliophile, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, whose extensive library was dispersed in the years following his assassination in 1897.

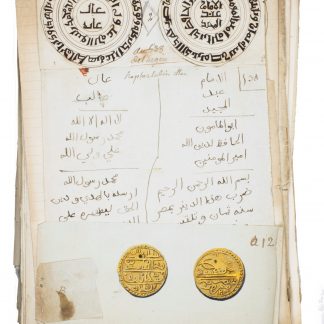

Partially removed ex-libris of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (1828-97). For the importance of Cánovas del Castillo as a book collector at the end of the 19th century see the article "Cánovas del Castillo juzgado por sus libros", España Moderna, 1907, pp. 60-92, written by Benito Pérez Galdós, the 19th century novelist and author. Stamped onto the remains of the bookplate is the bookstamp of the Madrid bookseller, Gabriel Sánchez. US private collection.

A. Muro Orejón & J. Hernández Díaz, El testamento de don Hernando Colón y otros documentos para su biografía, 1941. Guillén Torralba, Hernando Colón: humanismo y bibliofilia, Seville: Fundación José Manuel Lara, 2004, p. 101. Catálogo de … Gabriel Sánchez, 31. Marín Martinez et al., Catálogo concordado de la biblioteca de Hernando Colón (Madrid: Fundación Mapfre, 1993), I, 265f. Catálogo de algunos libros curiosos que pertenecieron á la biblioteca de Cánovas del Castillo y conserva uno de sus sobrinos (Madrid: Imprenta de Antonio G. Izquierdo, 1906), vol I.