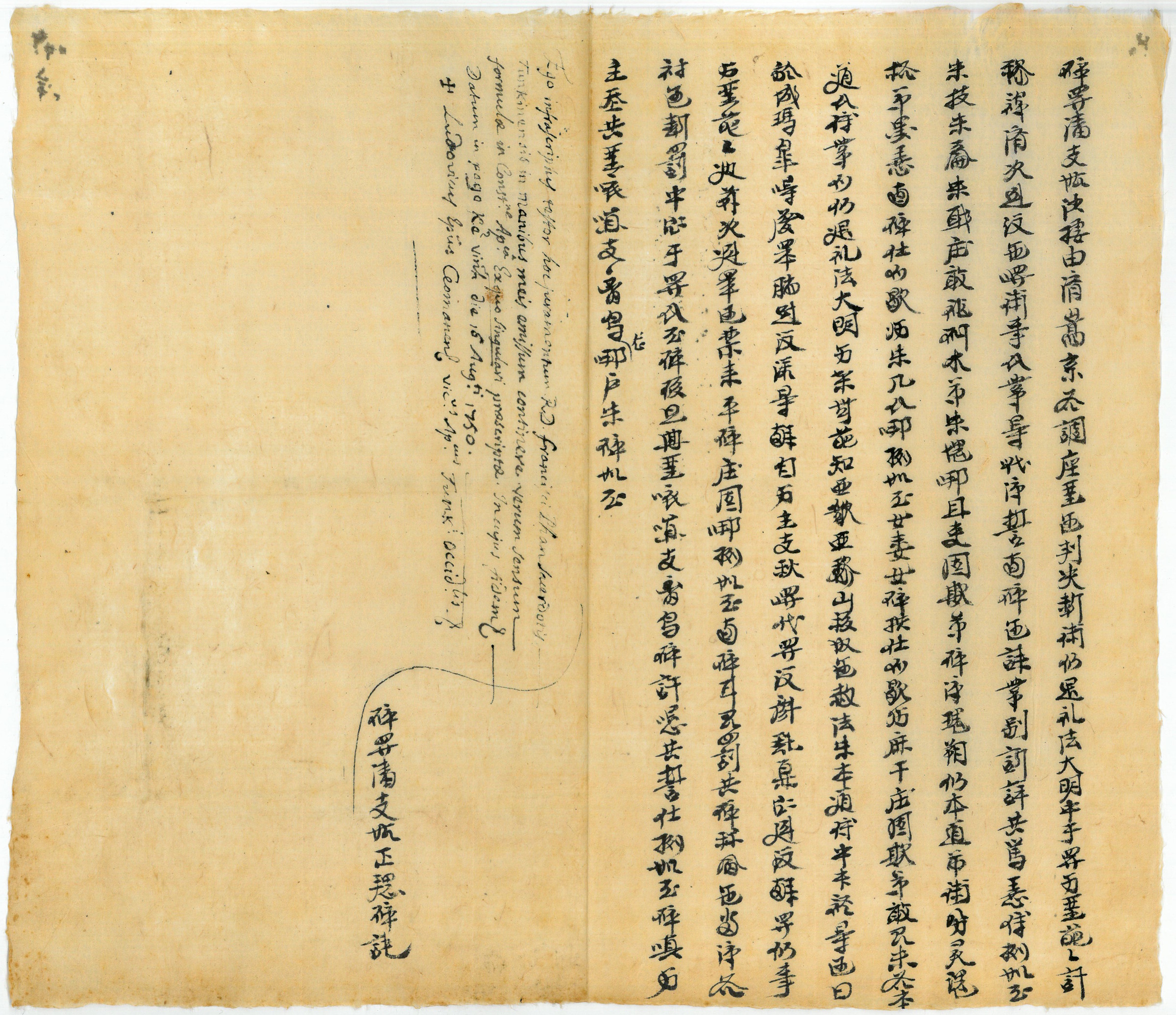

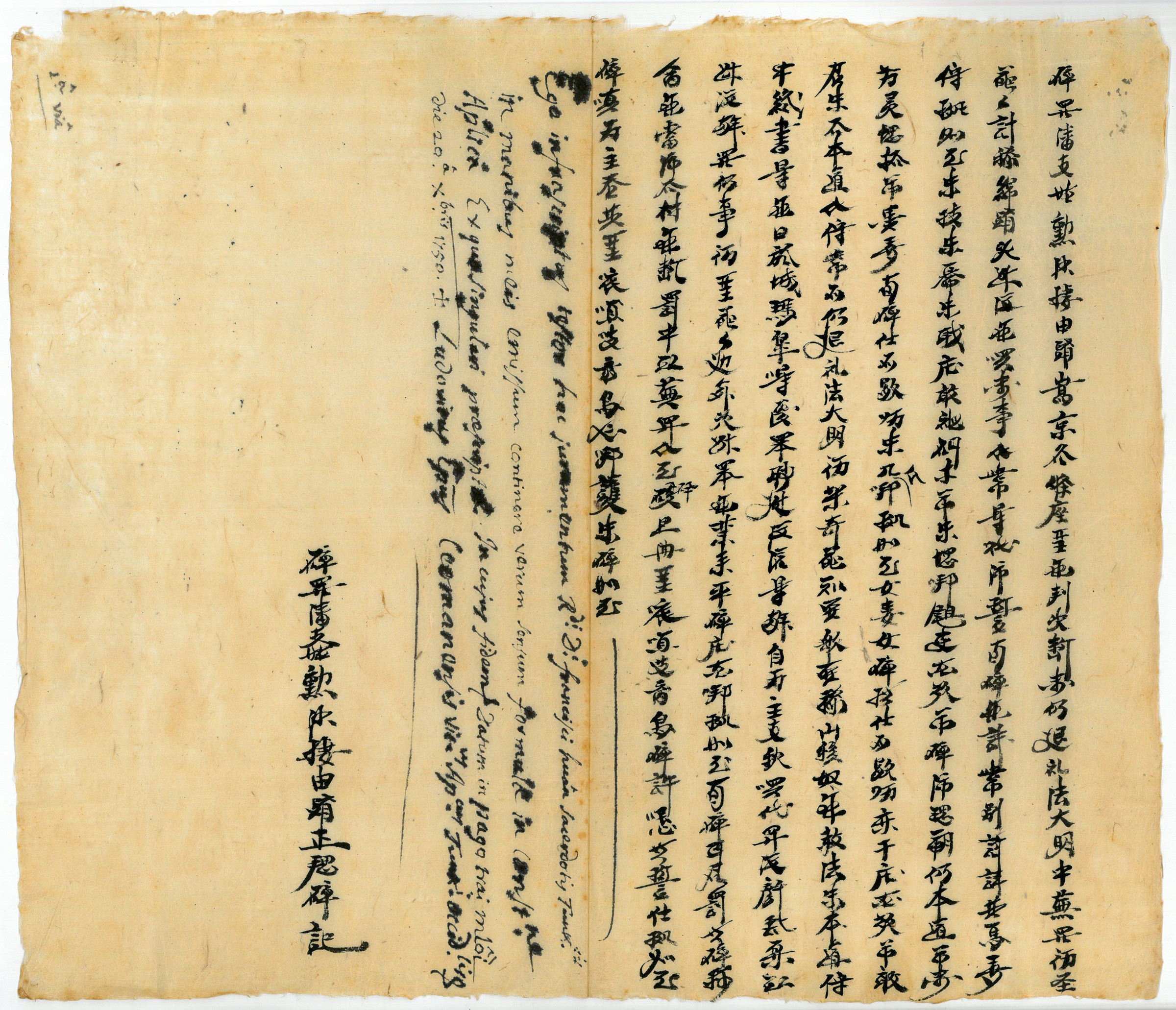

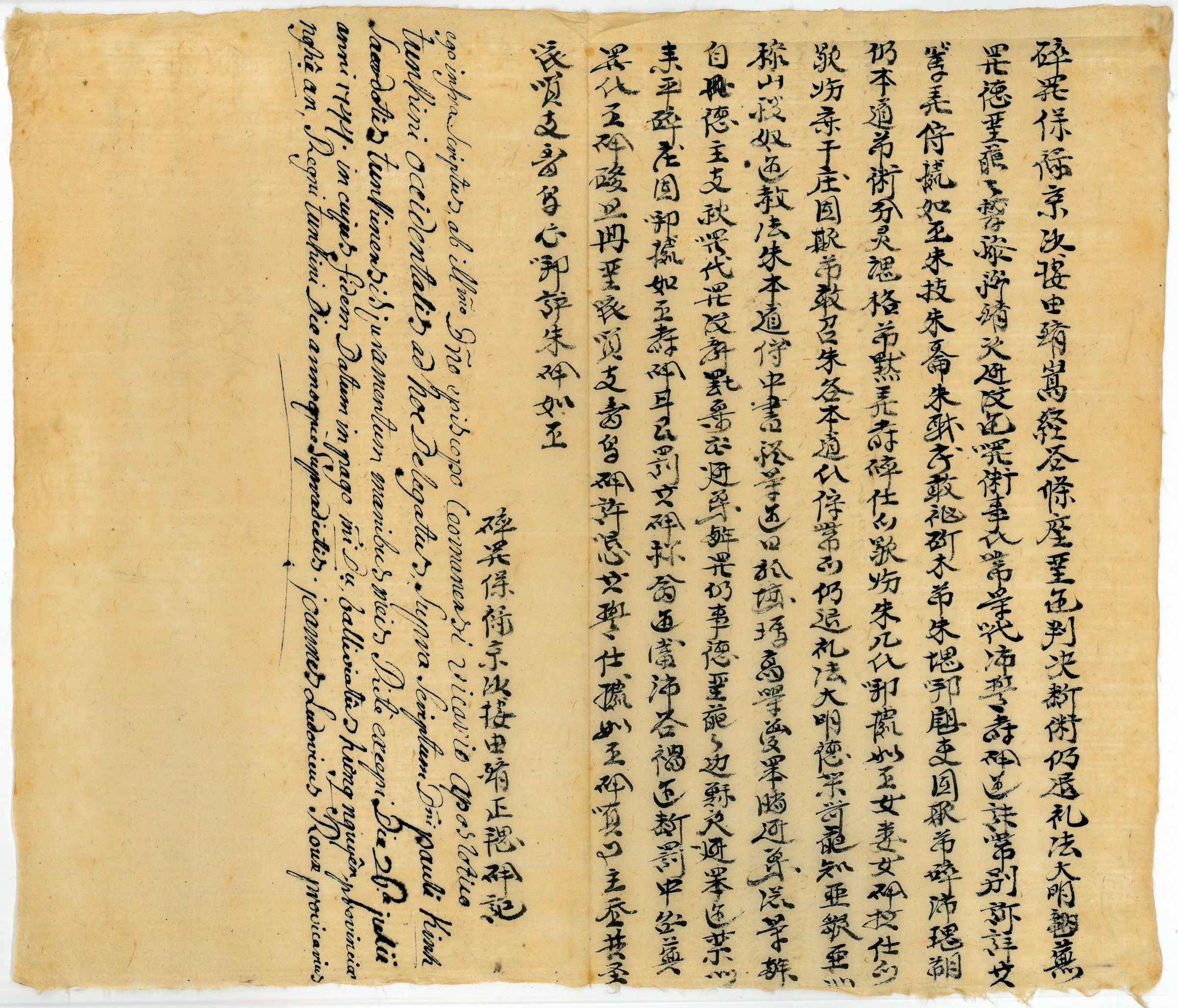

Autograph document signed. Co-signed by Jean-Louis Roux M.E.P.Tonkin, 26.07.1744.

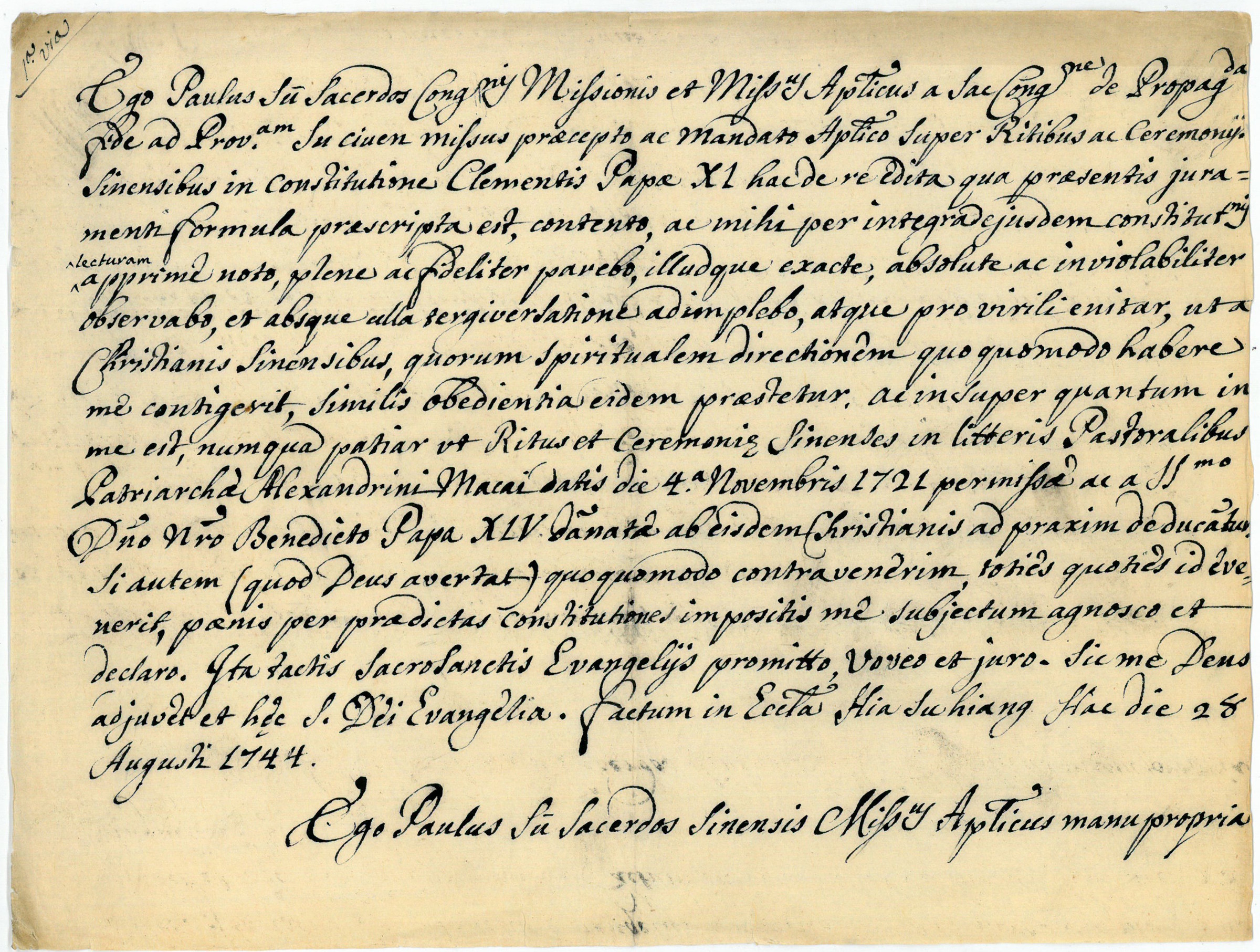

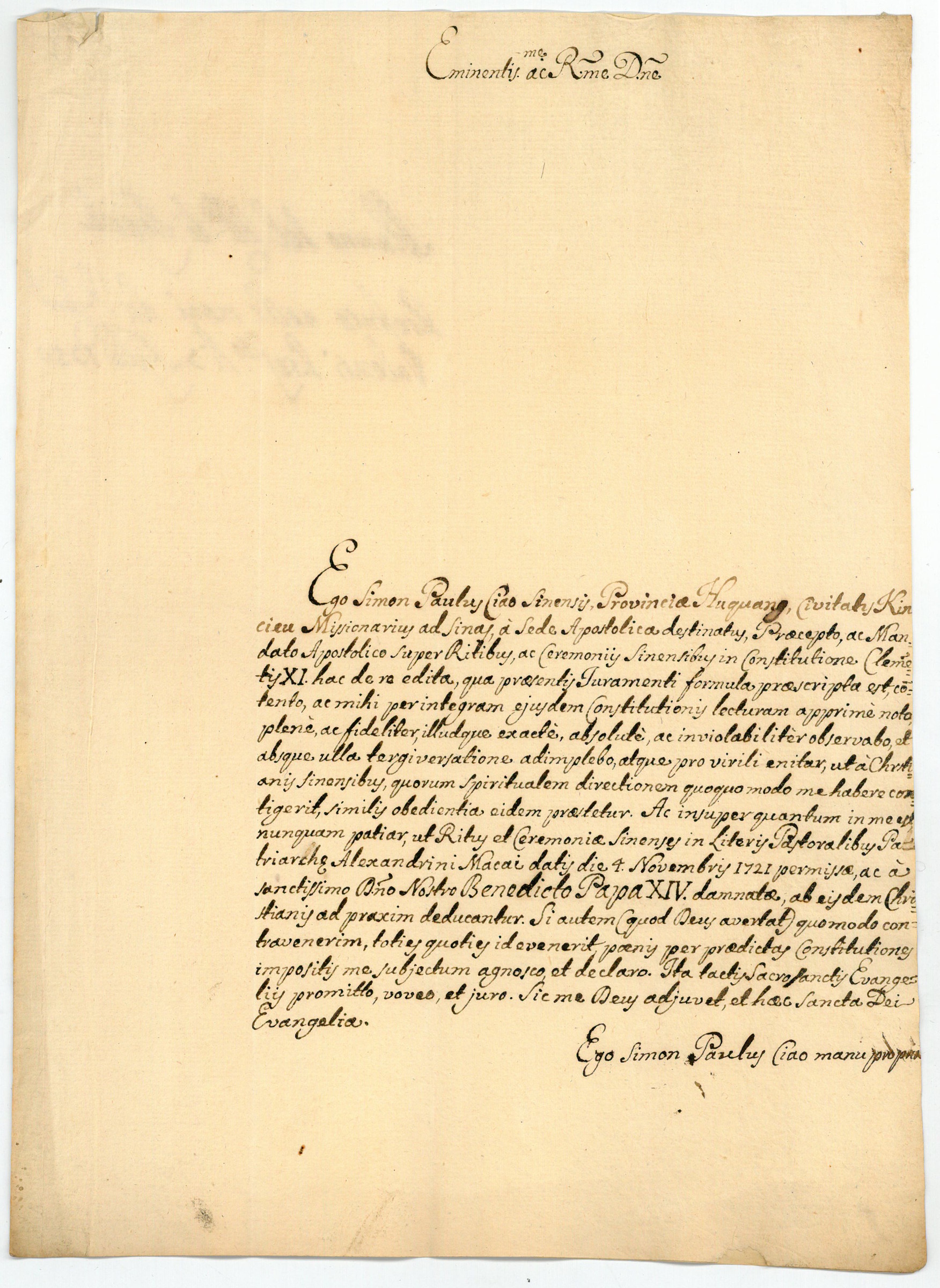

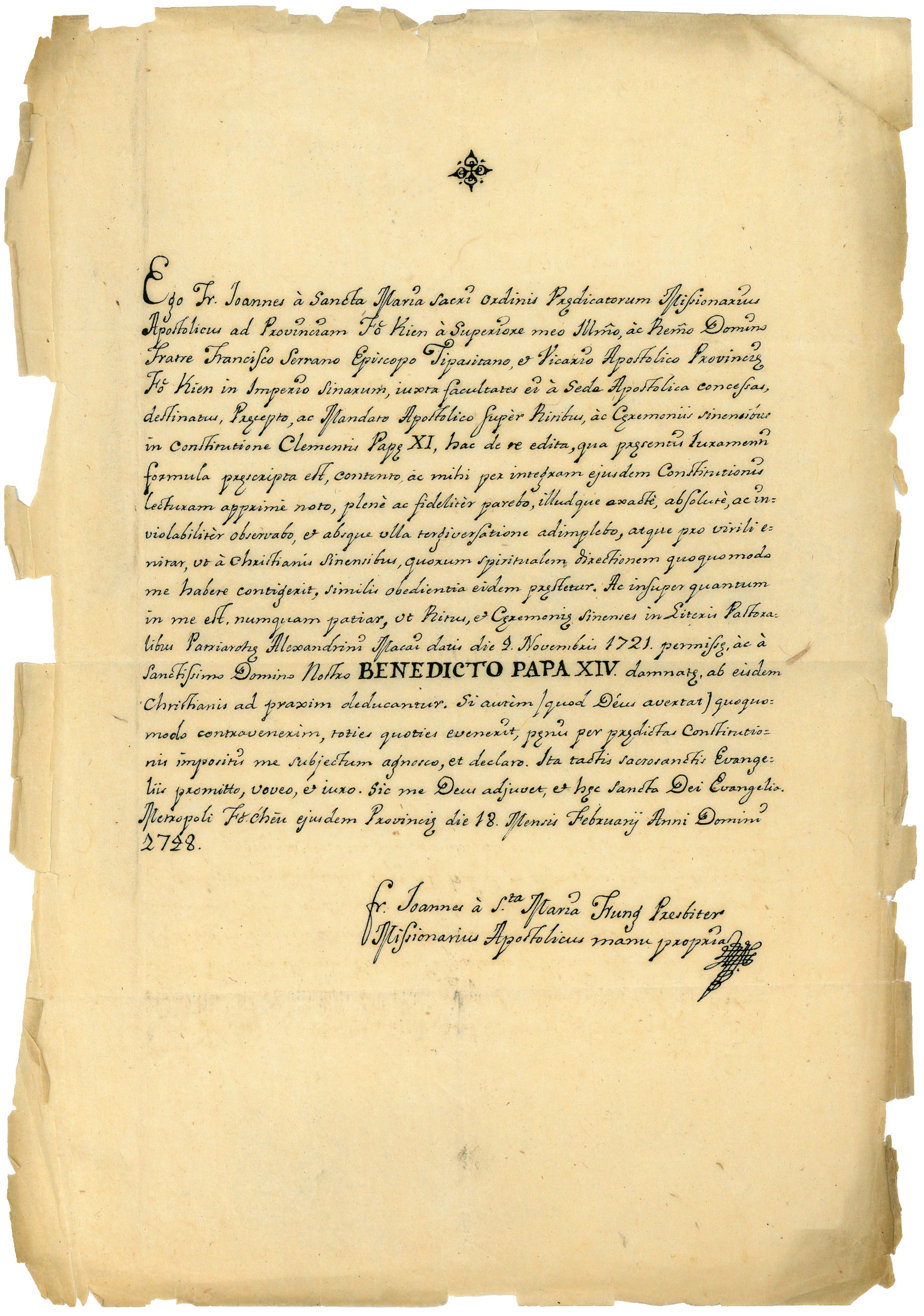

An oath renouncing the practice of the Chinese rites, taken by the Vietnamese missionary as required by the Papal Bull "Ex Quo Singulari" (1742). The oath was sworn on the Bible, and a form signed in one's own hand ("manu propria") had to be produced as evidence. Most of these documents are co-signed by church officials or senior friars as witnesses to an oath sworn in their presence ("in manibus meis"), in this case Jean-Louis Roux M.E.P. (1711-52), provicar in the Vicariate of Western Tonkin.

Paul Kinh was probably converted and trained by missionaries of the Paris Foreign Mission Society (M.E.P.) like Jean-Louis Roux. The Diocese of Western Tonkin in North Vietnam, today the Archdiocese of Hanoi, was erected in 1678 and led by M.E.P. missionaries until 1935. This beautifully calligraphed oath is an interesting document of French missionary work in North Vietnam and of the broader implications of the Chinese rites controversy in South East Asia.

During the early years of their mission to East Asia, the Jesuits led by Matteo Ricci accommodated Catholicism to Chinese customs and Confucian practice in important ways, both for political reasons and in hopes of attracting more converts. Criticism of this syncretism is as old as the Chinese rites themselves, and Ricci's direct successor Niccolò Longobardo attempted to change course, which led to his replacement as provincial. When Dominican and Franciscan missionaries entered China, they reported critically to Rome on the Jesuit practices. A first condemnation was decreed by Pope Clement XI in 1704 and confirmed in the 1715 Bull "Ex Illa Die". In "Ex Quo Singulari", Pope Benedict XIV re-affirmed "Ex Illa Die" and required all missionaries in East and South-East Asia to take the oath renouncing the practice of Chinese rites and similar accommodations to local beliefs and religious practice.