A foundational element in the development of written language

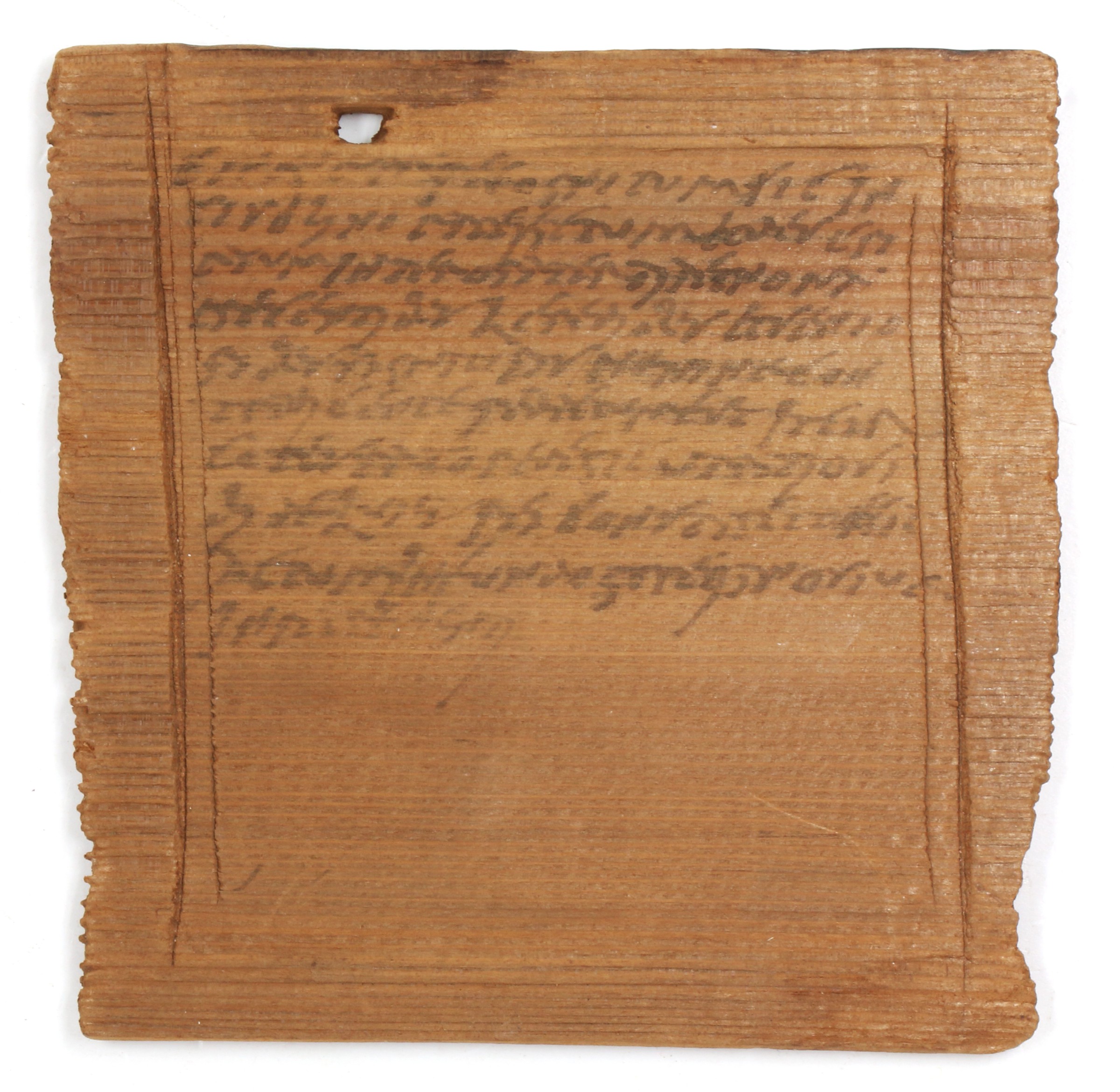

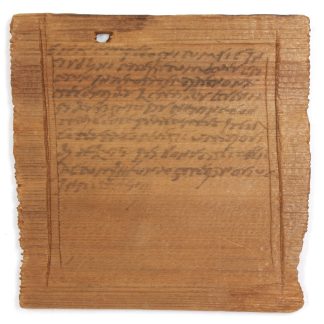

Roman inked wooden tablet.

Square wooden (probably cedar) tablet, ca. 125 x 124 mm. 10 lines of legal text, written in New Roman cursive script with a broad pen in dark ink on one side only, the natural grain of the wood serving as horizontal guiding lines for the writing. A reused tablet with a recessed panel on one side, forming the last tablet of a legal document which consisted of two or three tablets. Stored in a custom-made half-morocco case.

€ 95.000,00

One of the earliest extant documents in world history to be written in ink: a wooden tablet in New Roman cursive, the first true cursive script with minuscules. Succeeding the earlier, unsophisticated Old Roman cursive in the 3rd century, the style was quickly adopted as the daily script of the later Roman Empire and used widely beyond the official chanceries: not simply a stylistic variation, it is a foundational element in the development of written language in Western Europe and the ultimate precursor of all subsequent medieval minuscules, including our own lower-case alphabet.

Roman writing tablets were a crucial medium of communication in antiquity. Typically made from oblong pieces of wood pieces, they usually had a wax surface that was inscribed with a stylus. While the vast majority of ancient writing tablets is lost, examples of such wax slates ("tabulae ceratae") were discovered in Pompeii, and between 2010 and 2013 a significant collection was unearthed in London's financial district, dating from 50 to 80 CE.

Inked tablets, by contrast, are vastly more uncommon than wax examples. A trove of these remarkable slates was discovered in the fort of Vindolanda, south of Hadrian's Wall; each tablet is approximately the size of a modern postcard, and similarly thin. These specimens, now in the British Museum, are considered the earliest known surviving instances of ink-written letters from the Roman era.

The ink tablet at hand, however, represents a third group, the rarest of them all. The closest example are the "Tabulae Albertini", cedar wooden tablets which are larger and thicker than those from Vindolanda. Written in Northern Africa in the late 5th century CE, they were discovered in the region of Tébessa, Algeria, in 1928. The present tablet, however, is at least a century older, and although it has been reused, the recessed area never held any wax. No traces from earlier writing with a stylus is evident, so the previous text was probably washed off - a common practice with the ink tablets.

In his Historia Naturalis (book 35, §25), Pliny gives a classic account of "atramentum" ("ink", or literally, "blacking"), describing it as a mineral "made from soot in various forms, as (for instance) of burnt rosin or pitch ... The ink of the very best quality is made from the smoke of torches. An inferior article is made from the soot of furnaces and bath-house chimneys. Some manufacturers employ the dried lees of wine ... Polygnotus and Micon, celebrated painters at Athens, made their black paint from burnt grape-vines ... The dyers make theirs from the dark crust that gradually accumulates on brass-kettles. Ink is made also from torches (pine-knots), and from charcoal pounded fine in mortars ... Book-writers' ink has gum mixed with it, weaver's ink is made up with glue. Ink whose materials have been liquified by the agency of an acid is erased with great difficulty".

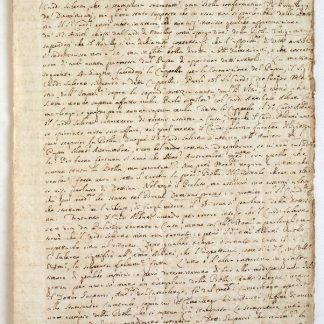

The text forms the end of a record of real estate transaction. Written in highly formulaic legal language, it confirms a contract between heirs and elders ("heredes et seniores") negotiated on an estate called "Rascotiano". The full document would have been a diptych or triptych, comprising two or even three tablets.

Acquired by Albert Sfez, Belgium, in the early 1950s, and gifted to the collection of his son Alain Sfez in 1965. In an important London collection since 1975.

One edge irregular. Pierced for addition of a thong or string. In excellent state of preservation. Accompanied by a collection of 18 photographs of the tablet (1970s).

Published in: Peter Rothenhöfer, Neue römische Rechtsdokumente aus dem Byzacena-Archiv / New Roman Legal Documents from the Byzacena Archive, (forthcoming). Cf. Peter Rothenhöfer, Jürgen Blänsdorf, "Sana mente sanaque memoria testamentum feci: Eine testamentarische Verfügung vom 12. April 340 n. Chr.", Gephyra 13 (2016), pp. 153-163; Peter Rothenhöfer, "Neues zum Testament des Pomponius Maximus aus dem Jahr 371 n. Chr." (forthcoming). See also Carla Masi Doria, "Dal testamento di Pomponius Maximus: prospettive del diritto ereditario tardo antico", in: Lisa Isola (ed.), Klauselgestaltungen in Römischen Testamenten (Berlin, 2022), pp. 151-175; J. D. Thomas, Vindolanda: The Latin Writing Tablets, Britannia Monograph Series No. 4 (London, 1983) for examples of wooden tabulae re-used as writing surfaces. For examples of testamentary documents on wooden tablets that have survived, see FIRA III, p. 47; for Anthony Silvanus from 142 AD; also see BGU VII 1695 for Safinnius Herminus; for another from Transfynydd, North Wales, see Arch. Camb. 150, pp. 143-156; and see A. K. Bowman, Life and letters on the Roman frontier: Vindolanda and its people (London, 1994) for discussion of the uses of Roman writing tablets.