Unrecorded celestial atlas, made by a Jesuit missionary in China

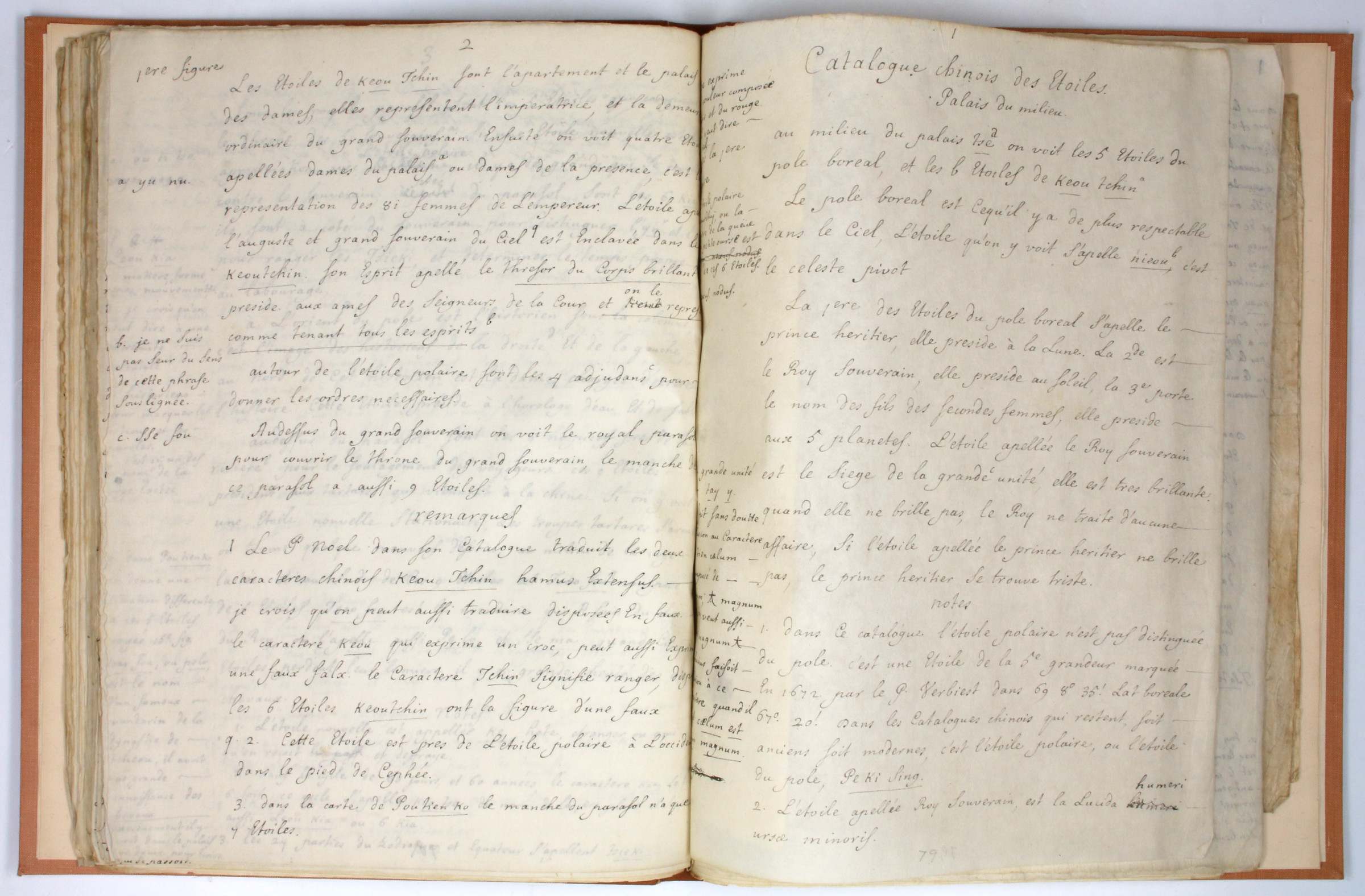

"Catalogue Chinois des Étoiles". Autograph manuscript.

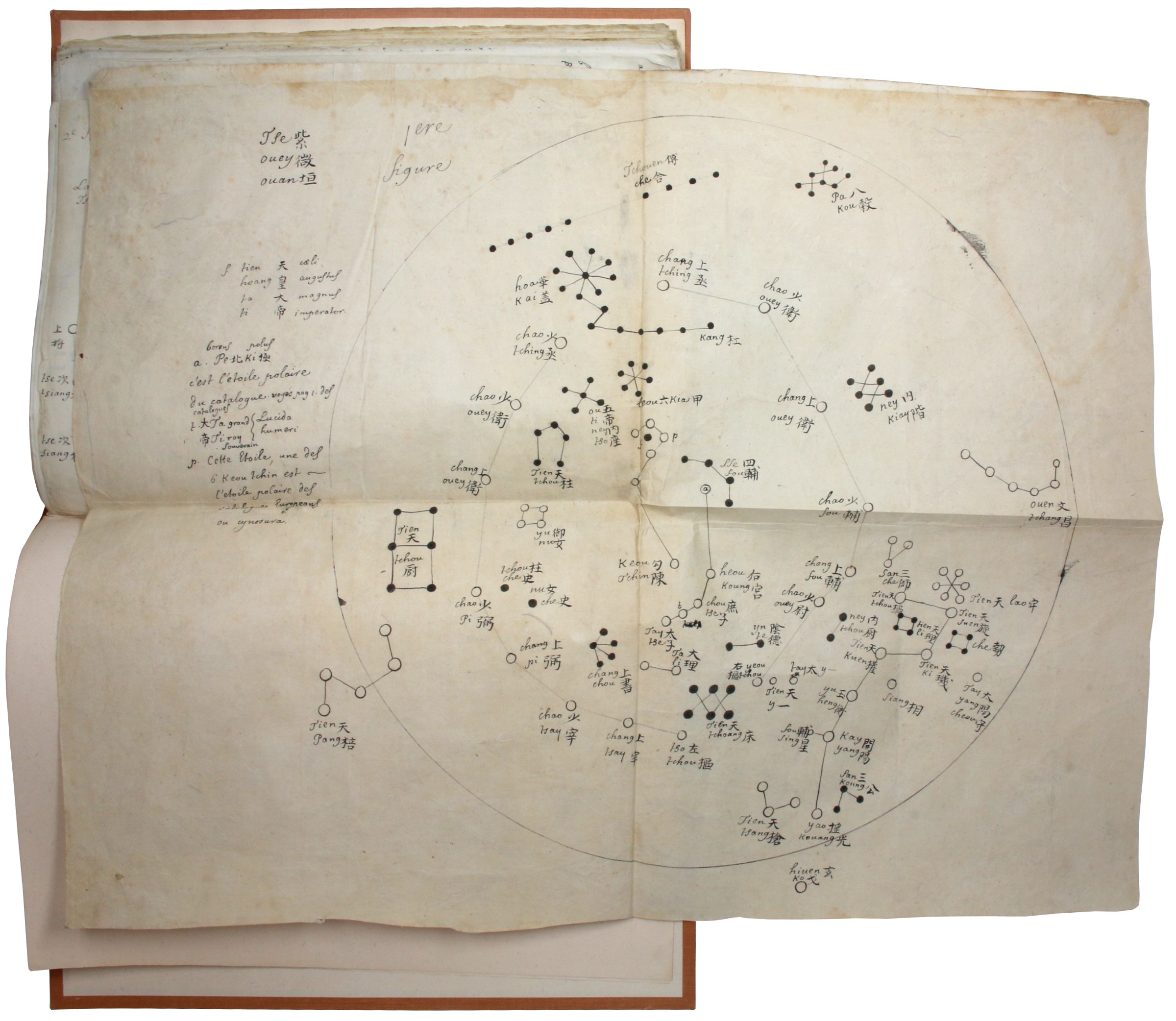

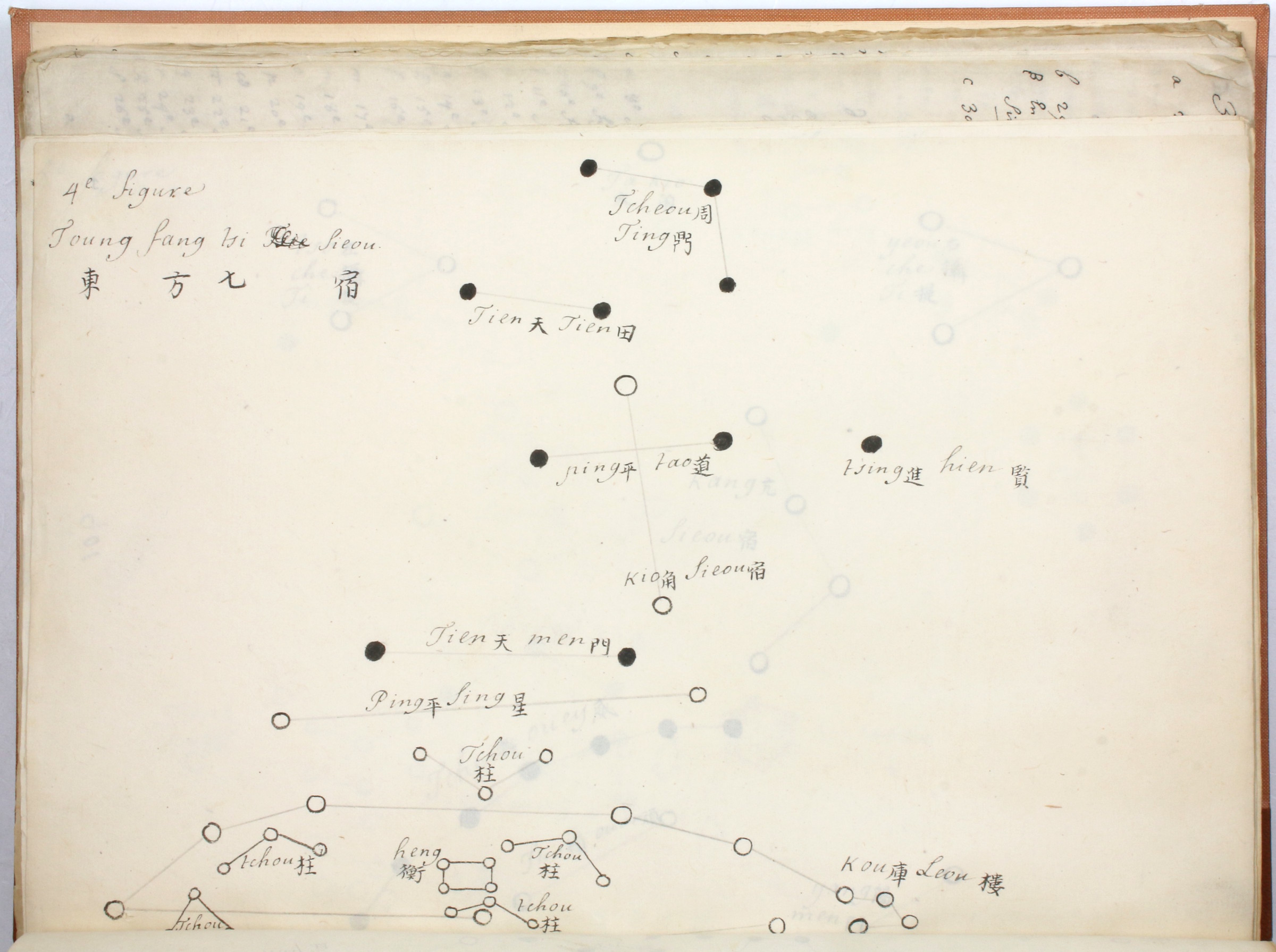

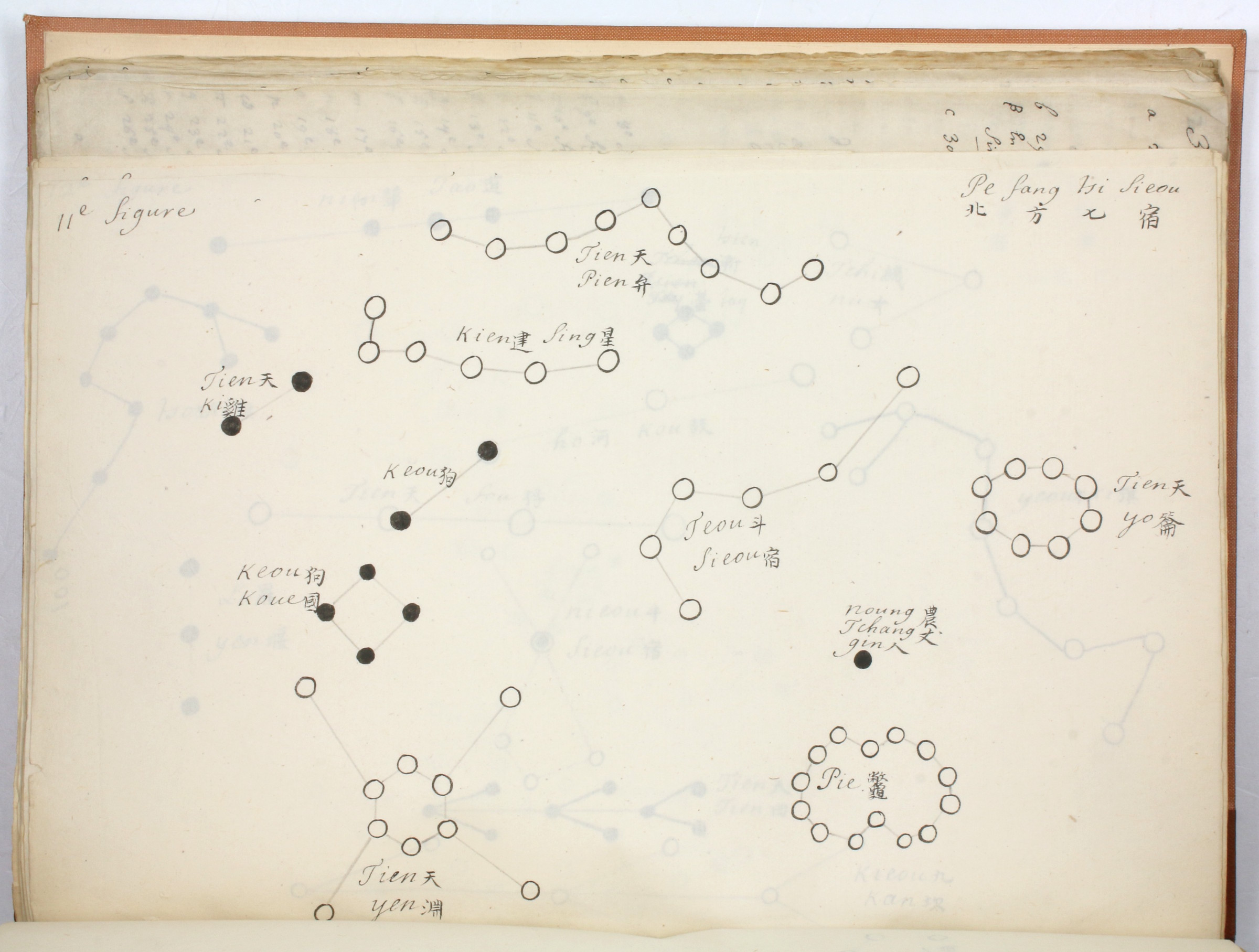

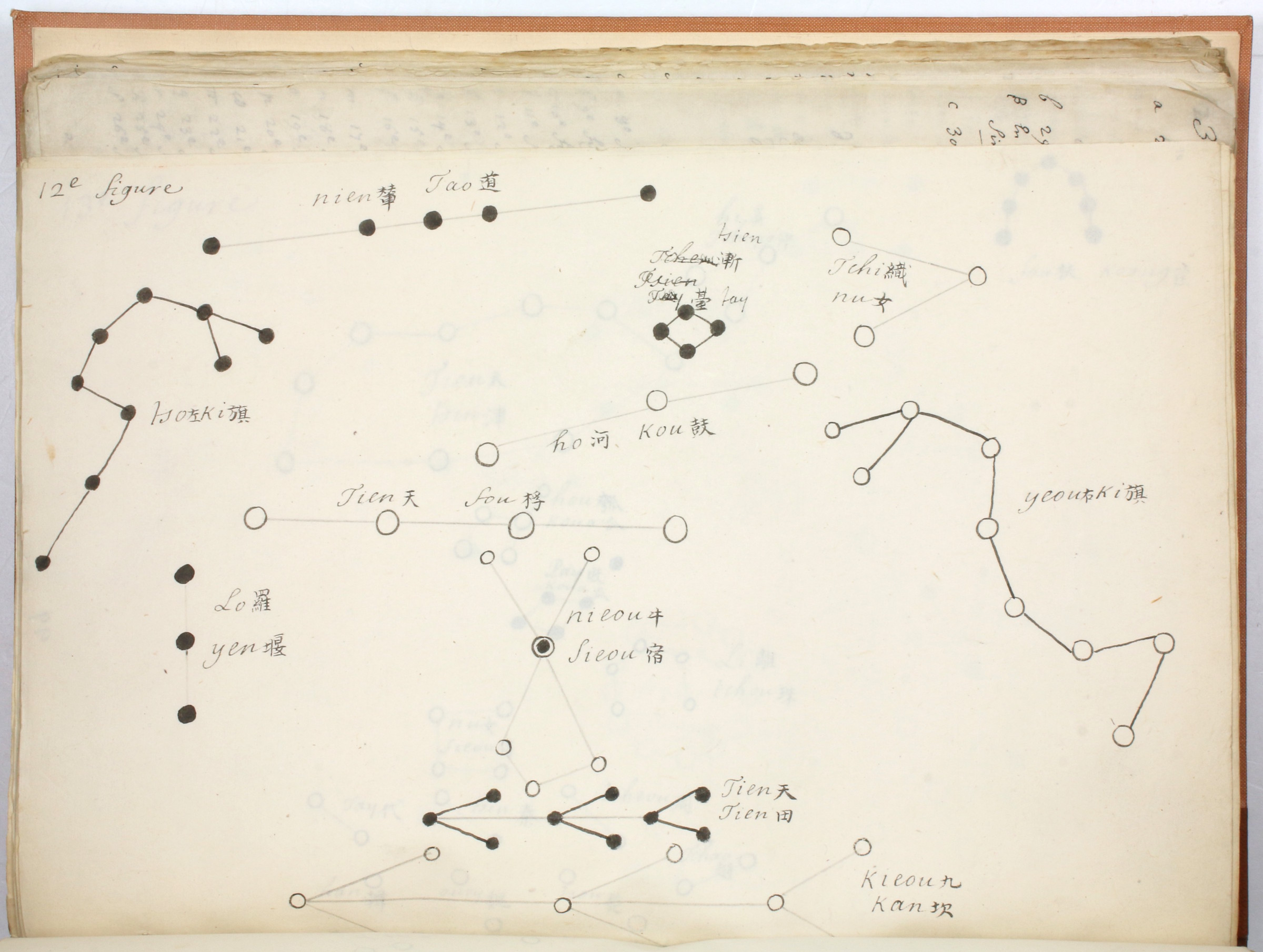

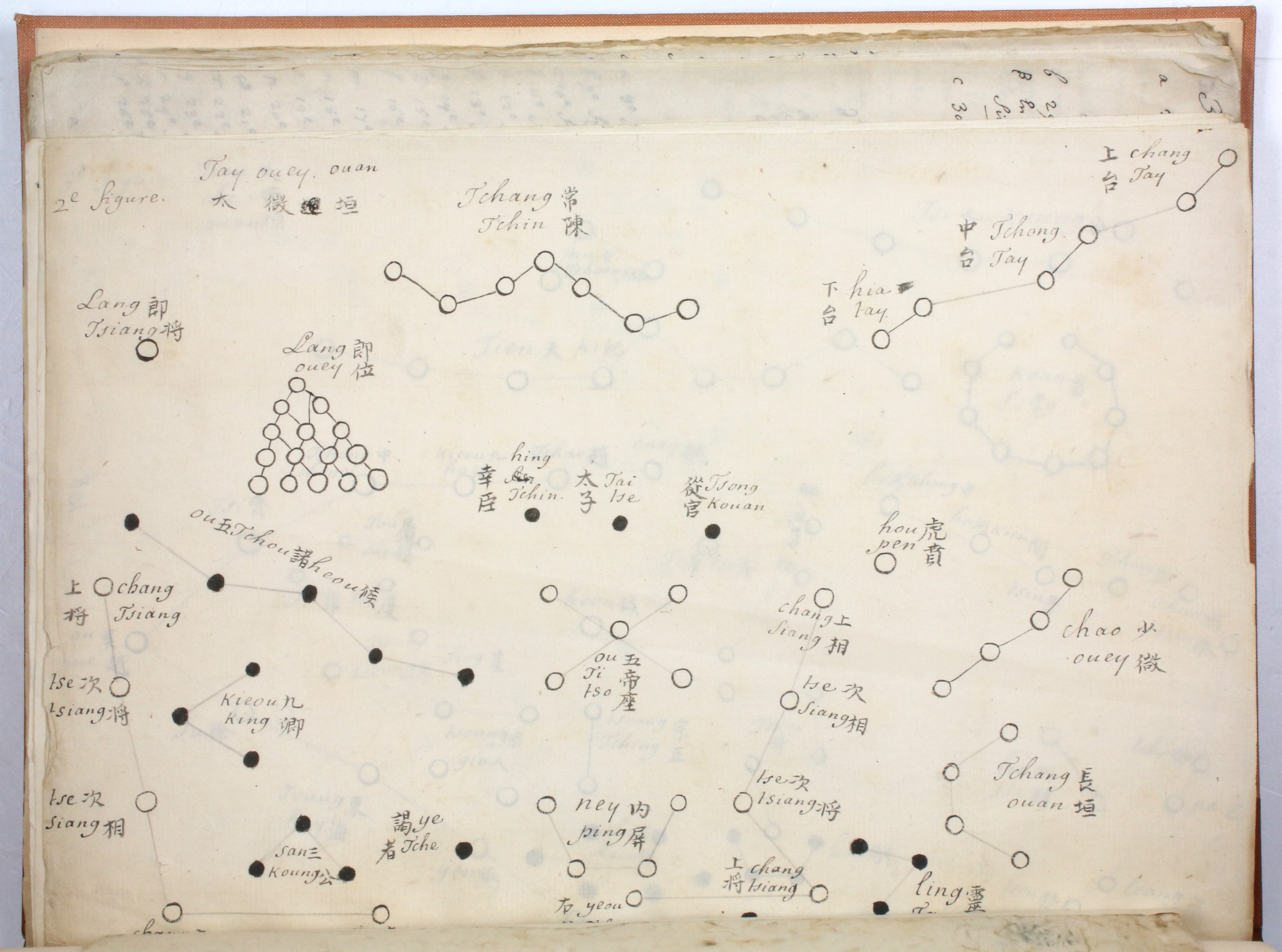

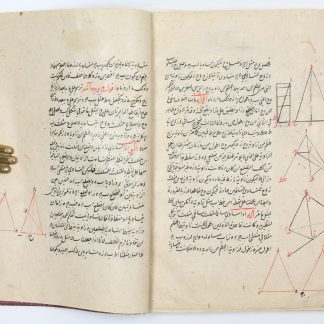

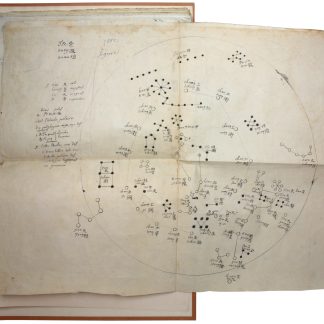

Folio (250 x 328 mm). French manuscript on rice paper. 78 (bound in reverse order), 3 pp. With 31 maps of stars and constellations, including 1 large fold-out diagram (ca. 540 x 435 mm). Modern quarter morocco, title in gilt on spine.

€ 125.000,00

An unrecorded manuscript celestial atlas from the Sui dynasty, edited with an extensive commentary by the early 18th century Jesuit astronomer Antoine Gaubil, hailed by Joseph Needham as the "father superior of Chinese Astronomy".

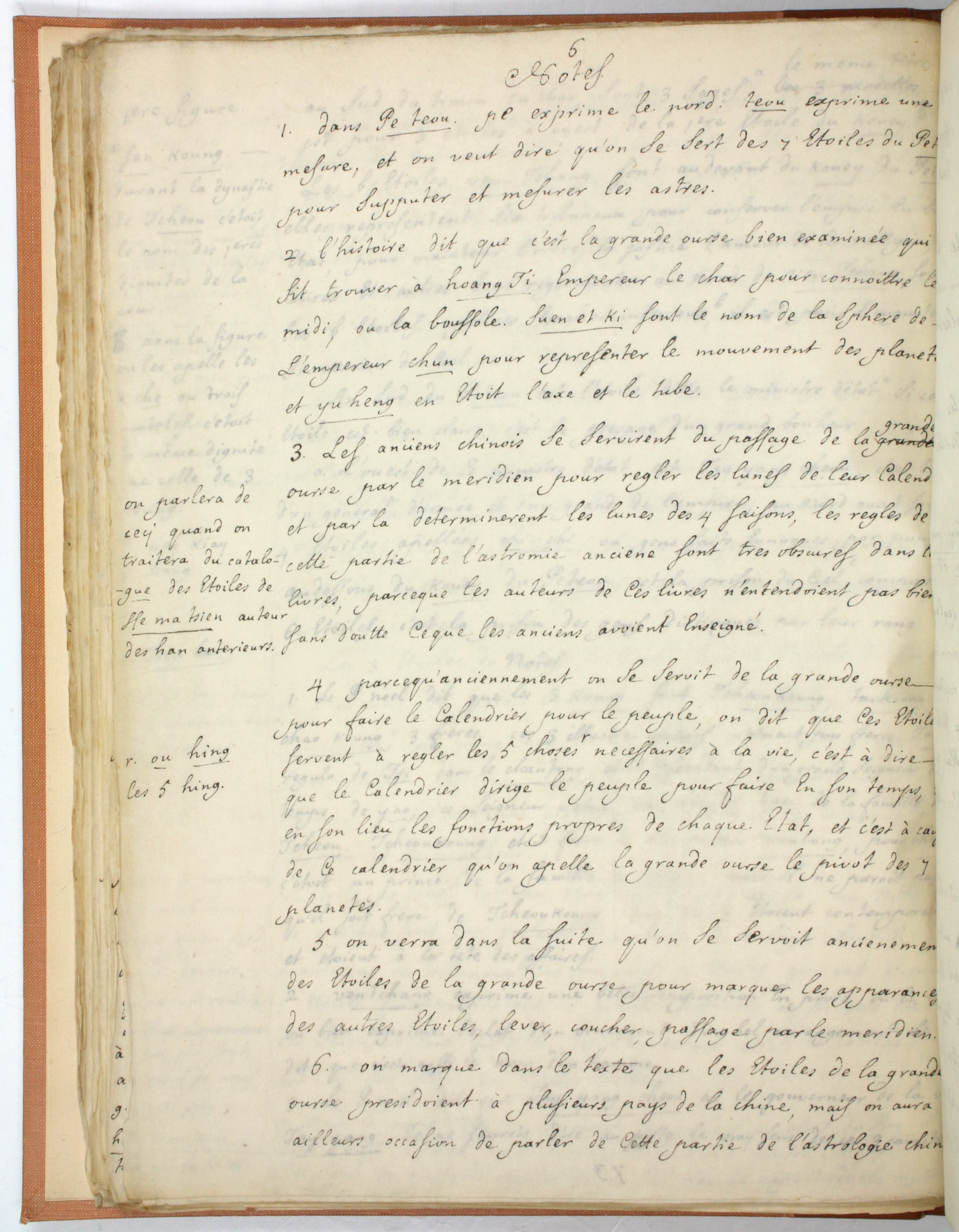

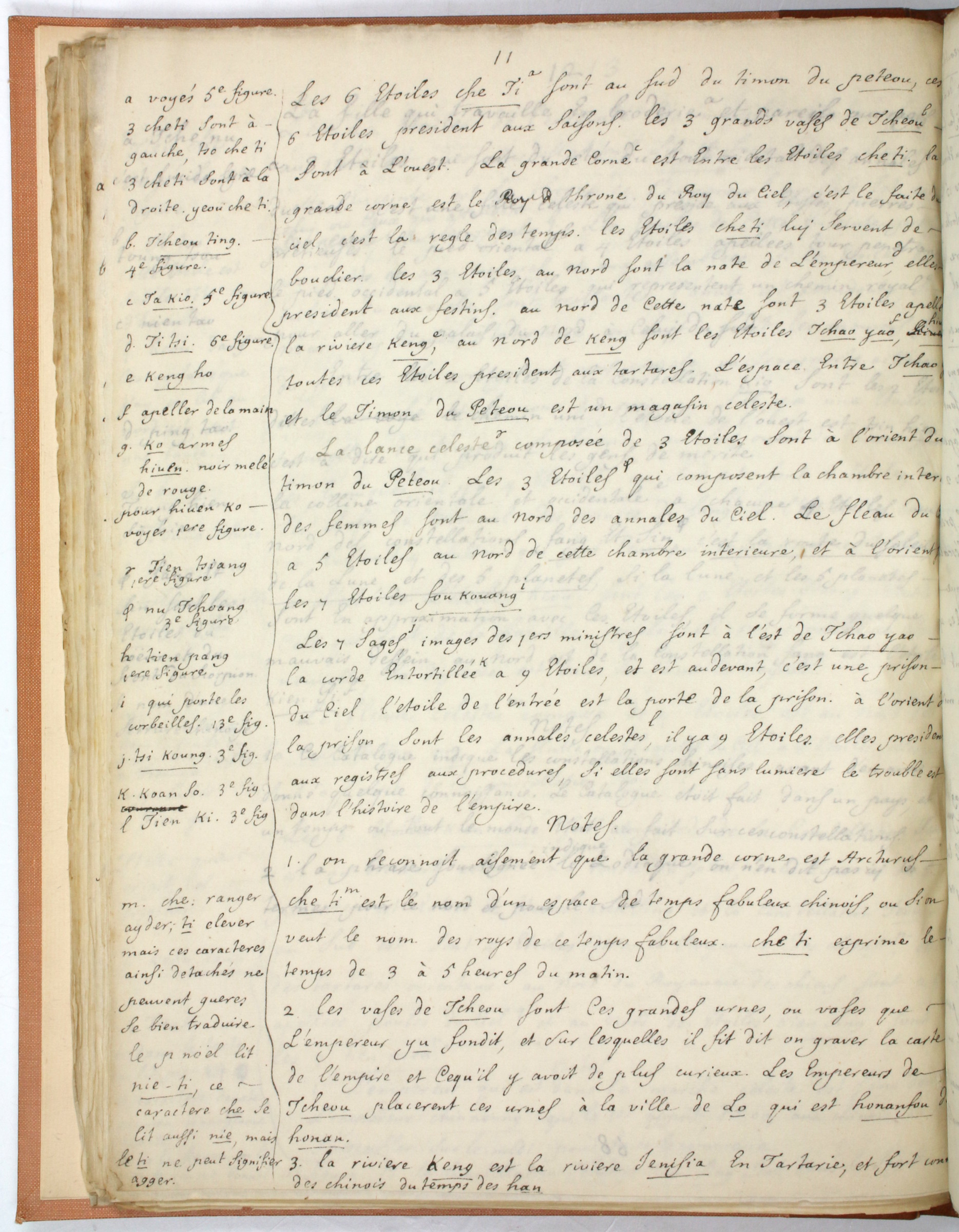

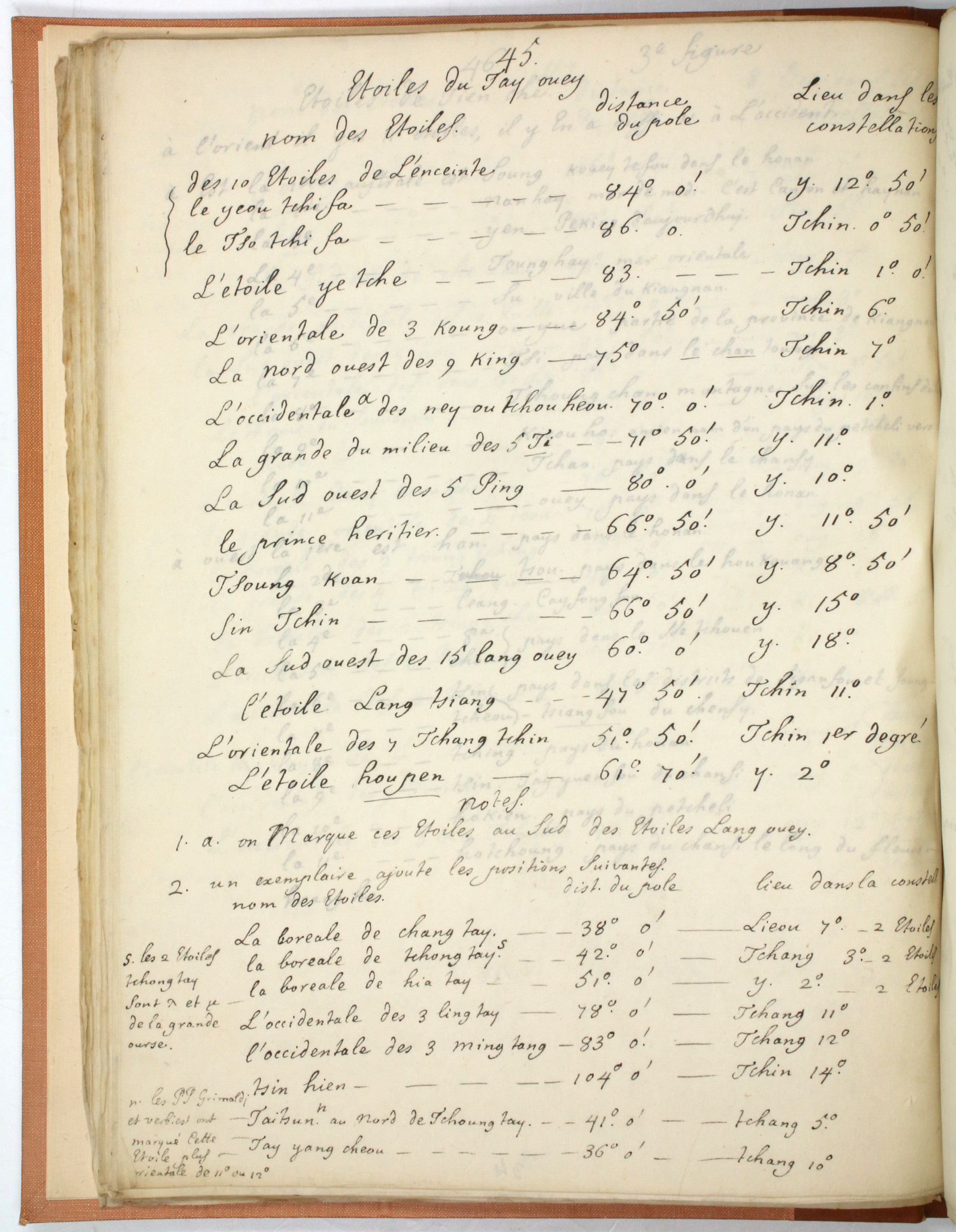

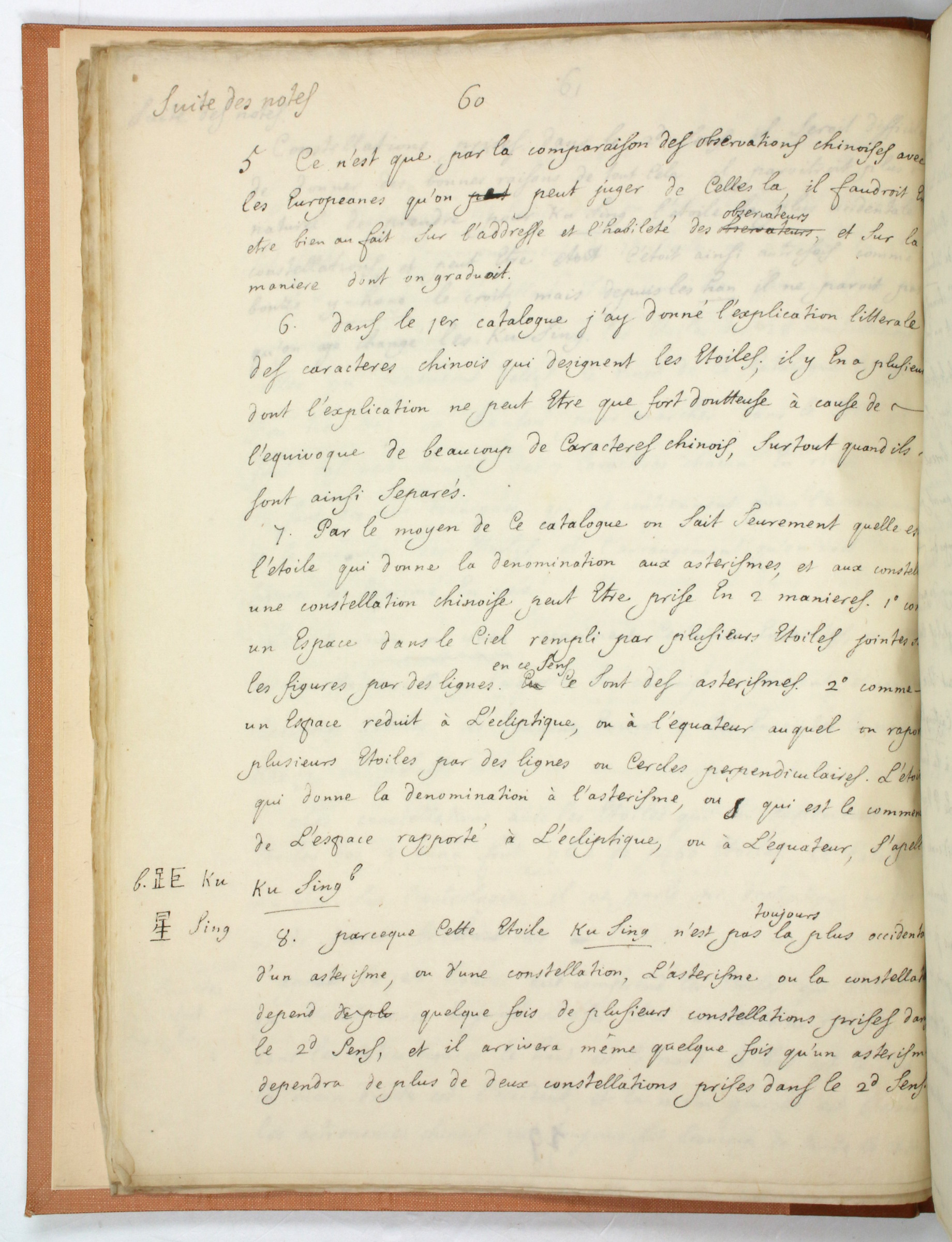

The manuscript contains an unpublished translation of the "Bu Tian Ge" (given in English variously as "Songs of pacing the heavens" or "The song of the marches of the heavens"), a Sui dynasty (581-618 CE) star catalogue in verse by the Taoist hermit Dan Yuanzi, also known as Wang Ximing. Beyond the text of the star catalogue, Gaubil provides his ink-drawn copies of 31 star charts, including a spectacular fold-out celestial map of the north polar region. Further, Gaubil offers not only an extensive commentary on the text, but also a tabular catalogue of Chinese stars that allows us to determine the corresponding European stars based on their distance from the North Pole.

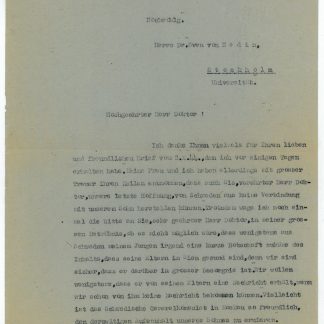

The manuscript can be dated securely to 1734, the year Gaubil sent it, together with the Chinese original, to the French astronomer Joseph-Nicolas Delisle in St Petersburg with a request that it be forwarded to his editor Étienne Souciet SJ (1671-1744) in Paris - a wish with which Delisle complied. Delisle's copy of the manuscript and the Chinese original, as well as the accompanying letter by Gaubil, dated Beijing, 25 July 1734, are preserved in the library of the Paris Observatory.

Written in verse, "Bu Tian Ge" was probably not intended for a scientific audience but rather to disseminate astronomical knowledge and to serve as a mnemonic. It is nevertheless "important in the history of Chinese astronomy because it definitely codifies the subdivision in the celestial skies into 3 yuan (enclosures or barriers) and 28 essential xiu, thus delineating the original theoretical organization of ancient Chinese astronomy" (Iannaccone). The poem is a beautiful testament to the microcosm-macrocosm analogy in Chinese natural philosophy, walking the reader through palaces and other institutions of the Chinese Empire, linking stars and their constellations to the political organization of the state and its representatives. In this system, the first constellation is the middle or purple palace (Zi wei yuán) of the Celestial Emperor: "In the middle of the Zi palace are the 5 stars of the northern pole, and the 6 Gòuchén stars. The northern pole is the most respectable in the sky, and the star seen there is called Niu [Niu Xing], the celestial pivot. The 1st star of the northern pole is called the Crown Prince, and presides over the moon. The 2nd is the Sovereign King, presiding over the sun; the 3rd is named after the sons of the second wives, presiding over the 5 planets" (transl.). The constellations of the purple palace or Ziwei enclosure are represented in fig. 1, the spectacular fold-out celestial map of the north polar region. Although the illustrations and the text are from the same source, Gaubil remarks in a short introduction to the charts that they cannot be assumed to be identical with those of the Sui dynasty original: "It would be preferable if we had these figures as they were made by the author of Bu Tien Ge, but no doubt they have been altered". They are nevertheless part of a continuous tradition of Chinese star maps that includes very similar objects such as the Dunhuang star map, dated around 700.

In his extremely valuable notes, comments, and glosses, Gaubil provides highly erudite cultural contextualization and the key to connecting Chinese astronomy with its European equivalent. A particularly interesting note points to astrological beliefs tied to the specific form of celestial representation in the "Bu Tian Ge", while distancing Chinese astronomical scholars from astrology: "It should come as no surprise, therefore, to see stars honoured in this catalogue, for example Canopus. As we have seen, the catalogue assumes that the spirit or soul of certain great men resides in certain stars, and it is not surprising for beings to be honoured who are believed to have the power to procure happiness or misfortune. Chinese scholars have always been far removed from such ideas". Finally, Gaubil offers a history of Chinese star catalogues and charts, tracing them back to the legendary Shang dynasty (ca. 1600-1046 BCE) shaman Wuxian, here transcribed as "Vou Hien", and the historically documented early astronomers Gan De and Shi Shen, active in the 4th century BCE, but also documenting Jesuit contributions to his own day: "When the Jesuits entered the court of mathematics [Imperial astronomical bureau, Qintianjian], they examined the Chinese celestial maps in detail, by means of conferences with local astronomers. They were soon able to see the Chinese stars that corresponded to the European ones, and made celestial maps in the European manner for latitudes, longitudes, declinations and right ascensions. They did not put the figures on the maps, but joined the stars of the Chinese asterisms by lines. They took the positions of the stars from Tycho's catalogues, and made a Chinese catalogue according to the order of the signs, adding the stars near the southern pole, unknown to the Chinese". As part of this tradition, Gaubil mentions the star charts of Ferdinand Verbiest and Claudio Filippo Grimaldi, whose charts were also attached to the aforementioned letter to Joseph-Nicolas Delisle, as well as Ignaz Kögler's plan to execute such a work. With respect to the recent catalogue of the Belgian Jesuit François Noël, Gaubil was somewhat skeptical: "Father Noël wrote a Latin catalogue of Chinese stars, but I do not think it is enough to explain what the Chinese know about stars".

Antoine Gaubil, who arrived in Beijing in 1722 and would remain there for the rest of his life, was the most important astronomer among the French Jesuits in China, and one of the greatest disseminators of Chinese science and wisdom in Europe in the 18th century. His work on astronomy and as an historian and translator of important Chinese texts such as the "I Ching" earned him the praise of Alexander von Humboldt as the wisest of the Jesuit missionaries. Joseph Needham even considers him "the interpreter general and father superior of Chinese astronomy", of which the manuscript at hand gives impressively evidence.

Formerly in the library of Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872). Dispersed over several decades in the 20th century, his manuscript collection is considered the largest ever privately assembled to this day.

Well preserved. The fold-out shows minor browning and creases.

Isaia Iannaccone, A Jesuit Scientist and Ancient Chinese Heavenly Songs, in: Historical Perspectives On East Asian Science, Technology And Medicine (Singapore University Press: Singapore, 2002), pp. 299-316. Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 3: Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth (Cambridge 1959).