Exceptional early Vitas Patrum, with a set of 275 woodcut illustrations in contemporary colour, here used for the time

[Vitas patrum - germanice]. Der altväter leben.

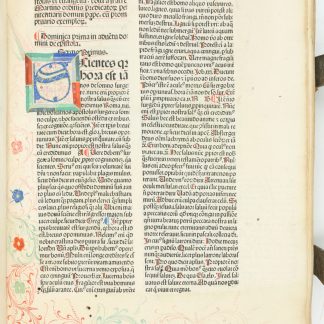

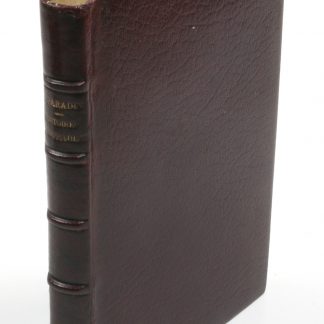

Folio (214 x 296 mm). 391 ff., lacking only the final blank, otherwise complete. With 19 large Maiblumen initials, large woodcut frontispiece and 275 woodcut illustrations, all in contemporary colour. Contemporary boards, original covering replaced in the 17th century with tooled Spanish leather, boards with supralibros and a complicated brocade design of parallel curved and straight lines, small squares and discs, fixed with a metallic film and glue, painted in reddish gilt, silver, and black; somewhat worn, joints restored, clasps removed, preserved in a dark green cloth Solander box.

€ 140,000.00

An influential early work on the lives of the Saints of Christendom, each woodcut in vibrant contemporary colour. The first edition with this illustration cycle; second German edition overall.

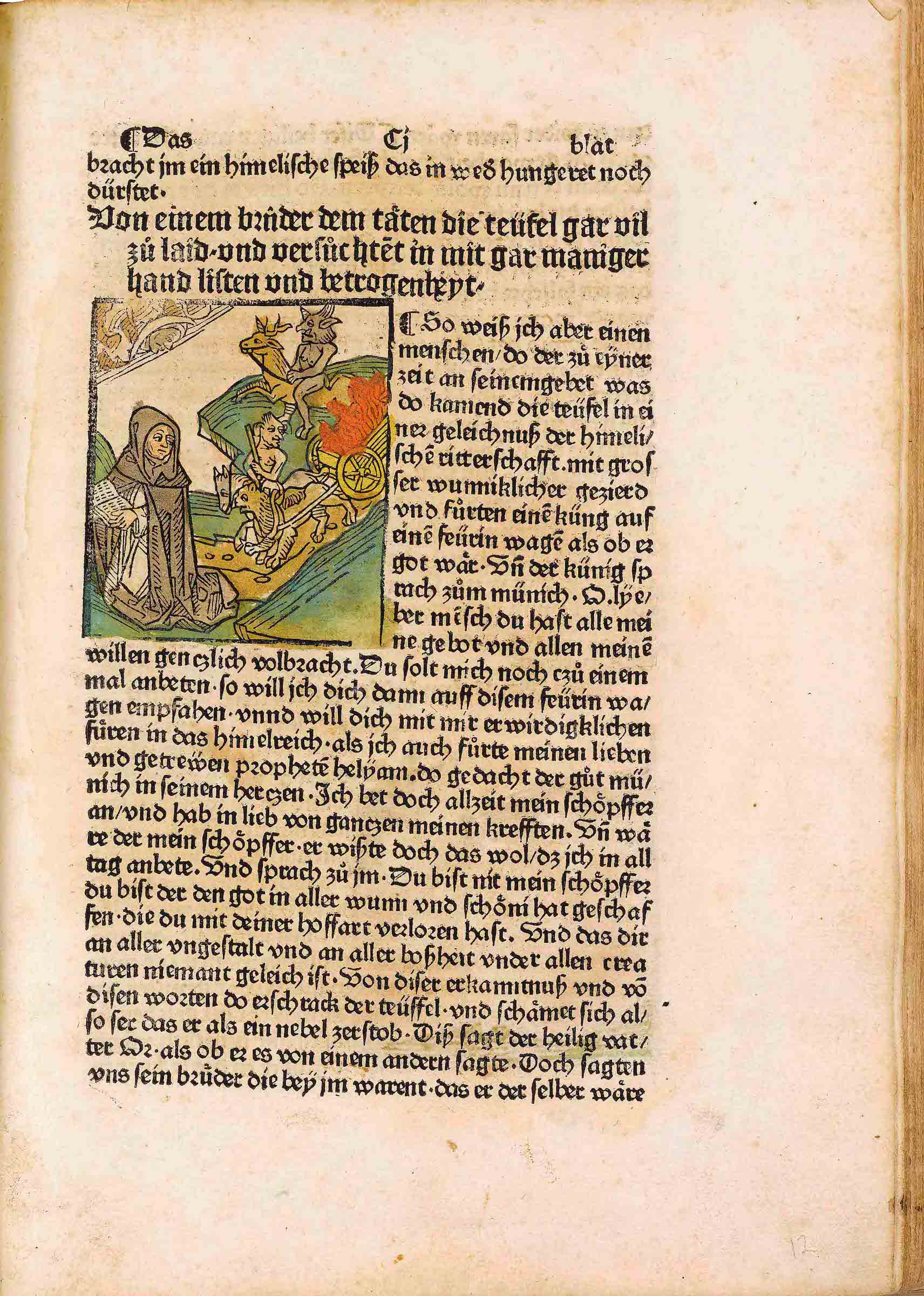

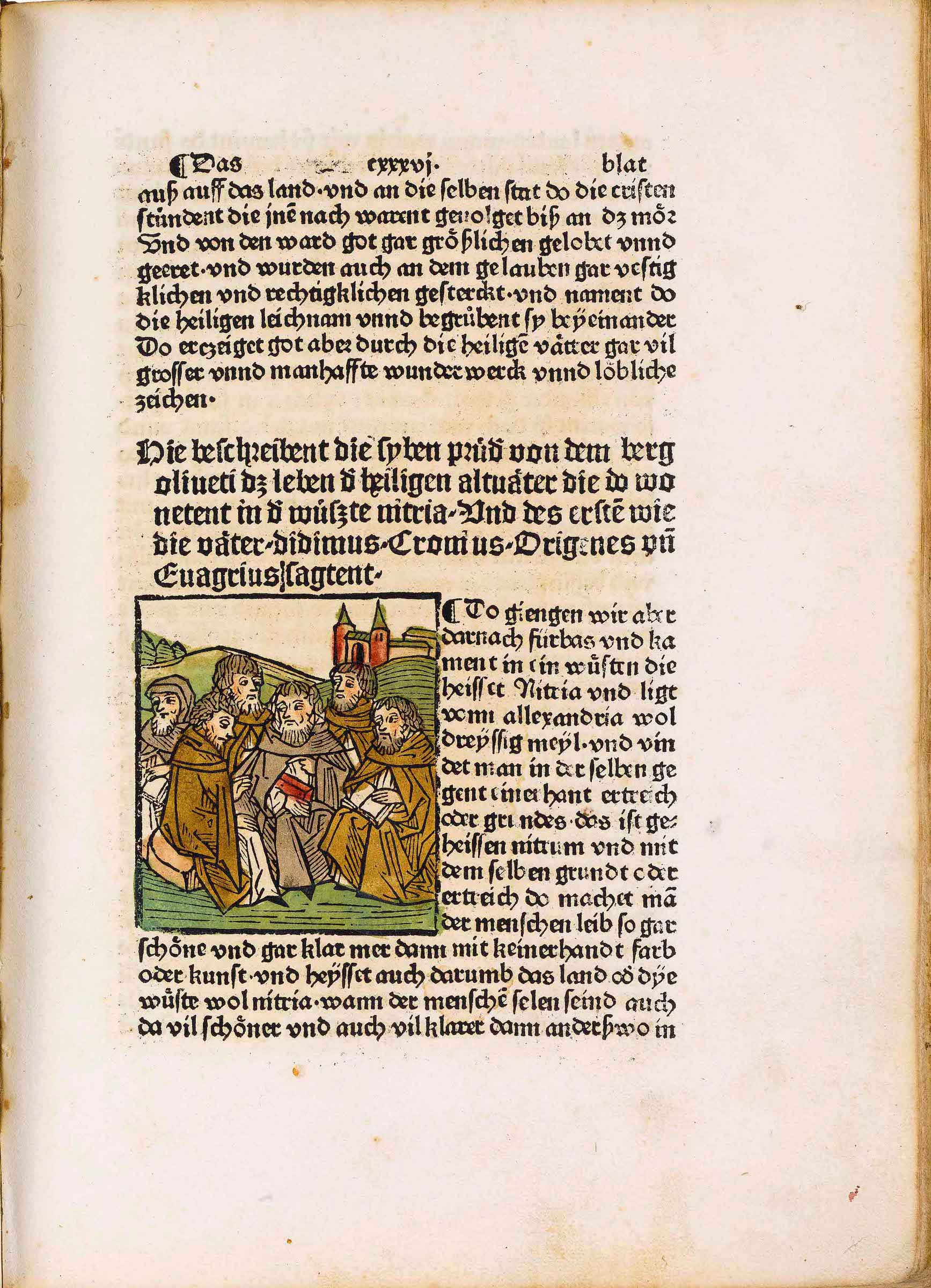

This stimulating work is a collection of biographies of the so-called Desert Fathers, both male and female: early Christian hermits who retreated from secular life into the deserts to practice ascetism and a life of devotion. The earliest versions of these "Vitae" were written in the third and fourth centuries and were extremely popular in early monastic circles. There was never a standardized order or set of these texts; rather, they were adapted according to the varying focuses of the convents for which they were made. A special appeal of the printed editions is the great number of often highly vivid woodcut illustrations, which made it easier and more enjoyable to read and hear these stories. Our copy is furthermore heightened with handsome contemporary colouring.

Transmitted under the Latin title of "Vitae sanctorum patrum" or "Vitas patrum", this collection consists of stories about early Christian hermits who, from the third century on, had retreated from cities and villages to the deserts of North Africa and Asia Minor to lead a life of devotion and ascetism. There was never a canonical combination of texts that formed the corpus of the "Vitas patrum"; instead, the choice of texts could vary according to the focus of the respective institution that owned the book. From the sixth century onward, the Rule of St. Benedict recommended the "Vitas patrum" as essential reading for monks. St. Dominic was ardently devoted to the lives of the Desert Fathers, and the influence of these texts on the development of Western monastic culture can hardly be overestimated. Virtually every monastery owned a copy of this "textbook for ascetism" (another designation for these compilations of narratives). In the Middle Ages, these accounts of the lives, deeds, and sayings of the Saints were attributed to St Jerome, although he in fact wrote only three of the biographies: he was responsible for the lives of SS. Hilarion, Malchus, and Paul the Hermit.

The present German edition was preceded only by the one printed in Strasbourg before 1482, by the unknown "printer of the Antichrist". That edition contained only a reduced number of exempla from the original collection, but boasted sayings from sources other than the "Vitas patrum", making this a different and shorter work. For the considerably extended Augsburg edition at hand, the printer Anton Sorg added the Bavarian "Verba seniorum", a collection of about 750 exempla originating in Bavaria, ca. 1400. The printer’s purpose was clearly to offer the most complete combination of the German texts on the subject. Apparently, this edition satisfied the demand with regards to content, as later editions were not augmented.

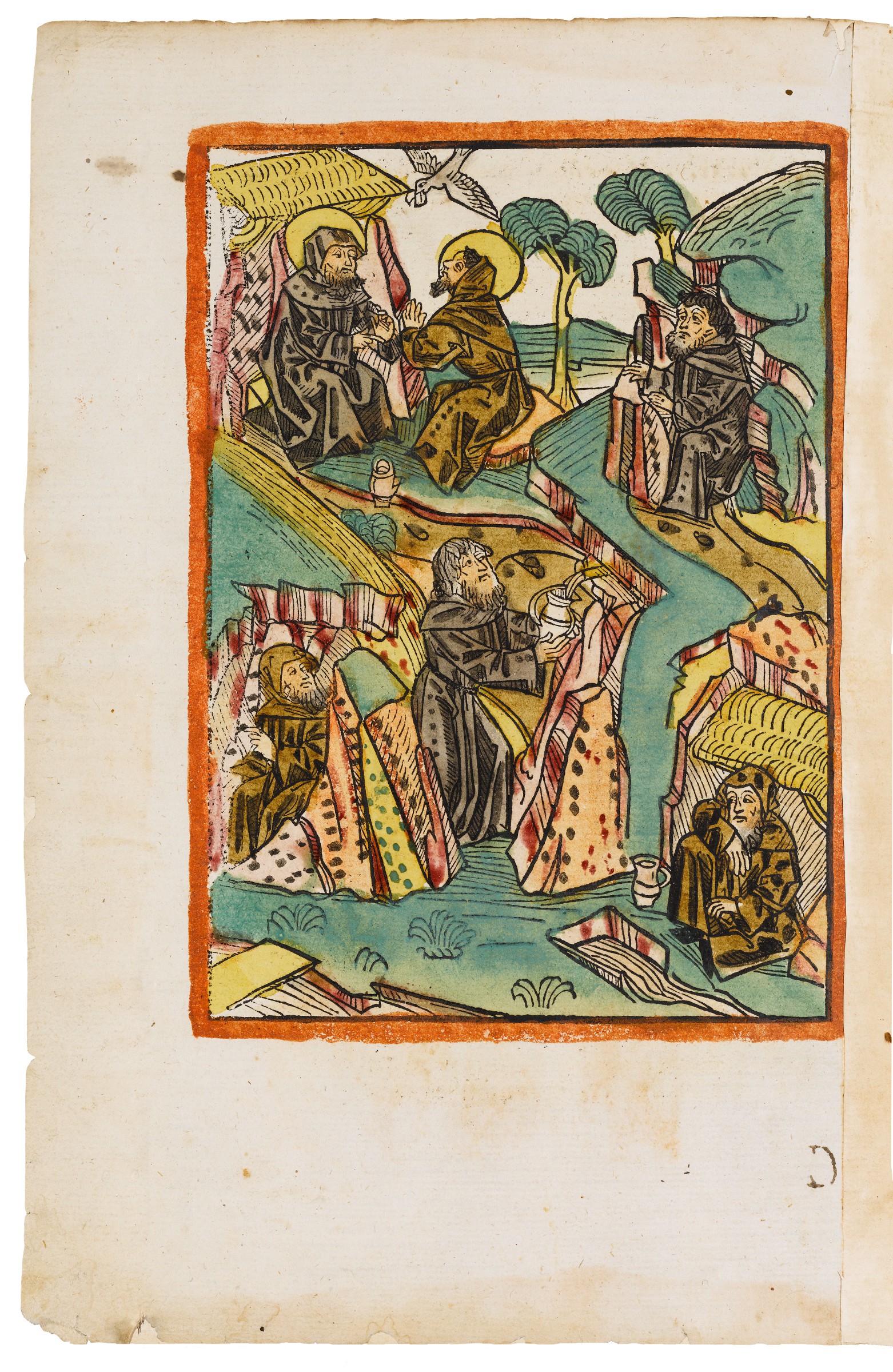

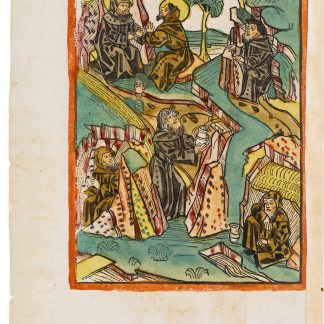

This is one of the most lavishly illustrated incunables printed in Augsburg. It is adorned with 276 woodcuts printed from 204 blocks. The opening full-page woodcut depicts six of the hermits in a landscape; apart from the full-page title cut (195 x 140 mm) and the author portrait showing St. Jerome (100 x 80 mm), the text illustrations measure ca. 73 x 68 mm.

Many of the stories are long adventures, calling for more than one illustration. The story of Malchus the monk, for example, is accompanied by four illustrations: against the insistent warnings of the abbot, Malchus leaves his convent in the desert to visit his native town in Syria to comfort his widowed mother. On their way, the travel group is taken captive by the Saracens. The abductors keep Malchus as their slave and shepherd, after a while urging him to marry a young Christian woman among the other captives. Since she is still married to another man, Malchus is appalled and tries to refuse the alliance. His captors threaten him badly, however, so he yields, and he and his new wife live together in chastity, eventually deciding to escape from the Saracens' camp. In preparation, Malchus slaughters two of his goats, makes bags of their skin, and takes the meat as supplies for their flight. On their way to freedom, they must cross a wide river, and they inflate the goat bags, floating to the other side in safety.

This narrative is remarkable because it invites the illustration of nudity, which would normally be considered indecorous within a pious book from a medieval point of view. While Adam and Eve and perhaps tortured martyrs might appear nude, the theme did not extend much further. Our story, however, explains that the Saracens' slaves were often naked, since their garments would fall to pieces and they were not provided with new ones.

The master of the Sorg cuts knew and used the Strasbourg compositions as models. It is clear that he did not make mere copies, but rather had to adapt the composition from a horizontal image to one that was nearly square. The resulting composition, focused squarely on the bodies in flight, offers a more vivid, physical illustration of the escape. The models for the second part, the exempla, must have been adapted from another source, possibly a manuscript, as the Strasbourg edition provided only four pictures for this part. It is also conceivable that the talented artist who designed the illustrations for the first part also invented the designs for the remaining woodcuts himself (cf. Musper, "Dialekte und Idiome im frühen Buchholzschnitt", Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 1940, p. 108).

All the illustrations and the large woodcut initials are in a beautiful contemporary colour. Specific details on the organization of hand colouring in Sorg's printshop are lacking; evidently, these enhancements were commissioned by the publisher or the retailer. Often, however, a buyer provided for the embellishment according to his own taste and means. In our case, we can find some similarities between the colouring of the Augsburg copy and the one at hand, which might suggest that the present book’s colouring also comes from Sorg's workshop. These magnificent woodcut sets proved popular, and re-appeared in 1492 in an edition printed by Sorg’s son-in-law, Hans Schobser, and later in 1488 by Peter Berger, 1485/87 and 1497 by Johann Schönsperger.

This work is very scarce in the trade and rarely found complete. Apart from the present copy, we could trace only one complete copy at auction since 1950 (1958, Karl & Faber, auction 65, lot 40a); the other five copies were imperfect (the last one 2007 at Christie’s). ISTC records 28 copies (four in the USA), at least 13 of which are incomplete or even fragmentary.

From Nonnberg Abbey, a Benedictine convent near Salzburg, with oval supralibros of Nonnberg showing St Erentrudis stamped on binding. Contemporary ownership inscription on pastedown and first leaf and a small stamp on the second leaf. Nonnberg is the oldest continuously existing nunnery north of the Alps. The convent was founded in 712 AD by St Rupert for his relative (probably his niece) St Erentrudis, the original abbess. As a religious house, it was forced to cede its finest manuscripts to the Royal Library in Munich during the secularisation of 1802-03. Moreover, like so many other Austrian monastery libraries, it sold books in the 1920s to meet rising costs and dwindling income.

Later owned by Emil Offenbacher (1908-90), New York, bookseller, who sold the book in 1954 to Cornelius J. Hauck (1893-1967) of Cincinnati, Ohio, a bibliophile primarily known for his collection of books on botany and horticulture.

A very fine copy with wide margins. The first 3 and final 2 quires re-sewn, with some leaves restored in the gutter, leaves I and CCCLXXXI repaired at lower and upper margin, respectively. Minor thumbing and soiling, occasional light damp-staining, some bleeding of colours in a few places.

H 8605*. GW M50901. Goff H-217. BMC II, 350. BSB-Ink V-259. Schreiber 4217. Schramm IV, pp. 26-30, figs. 285, 842-1045. Rosenwald collection no. 89. ISTC ih00217000.