The antagonist of the Jesuits at the Imperial Court in Beijing reports to Pope Clement XI on a fateful audience with the Kangxi Emperor

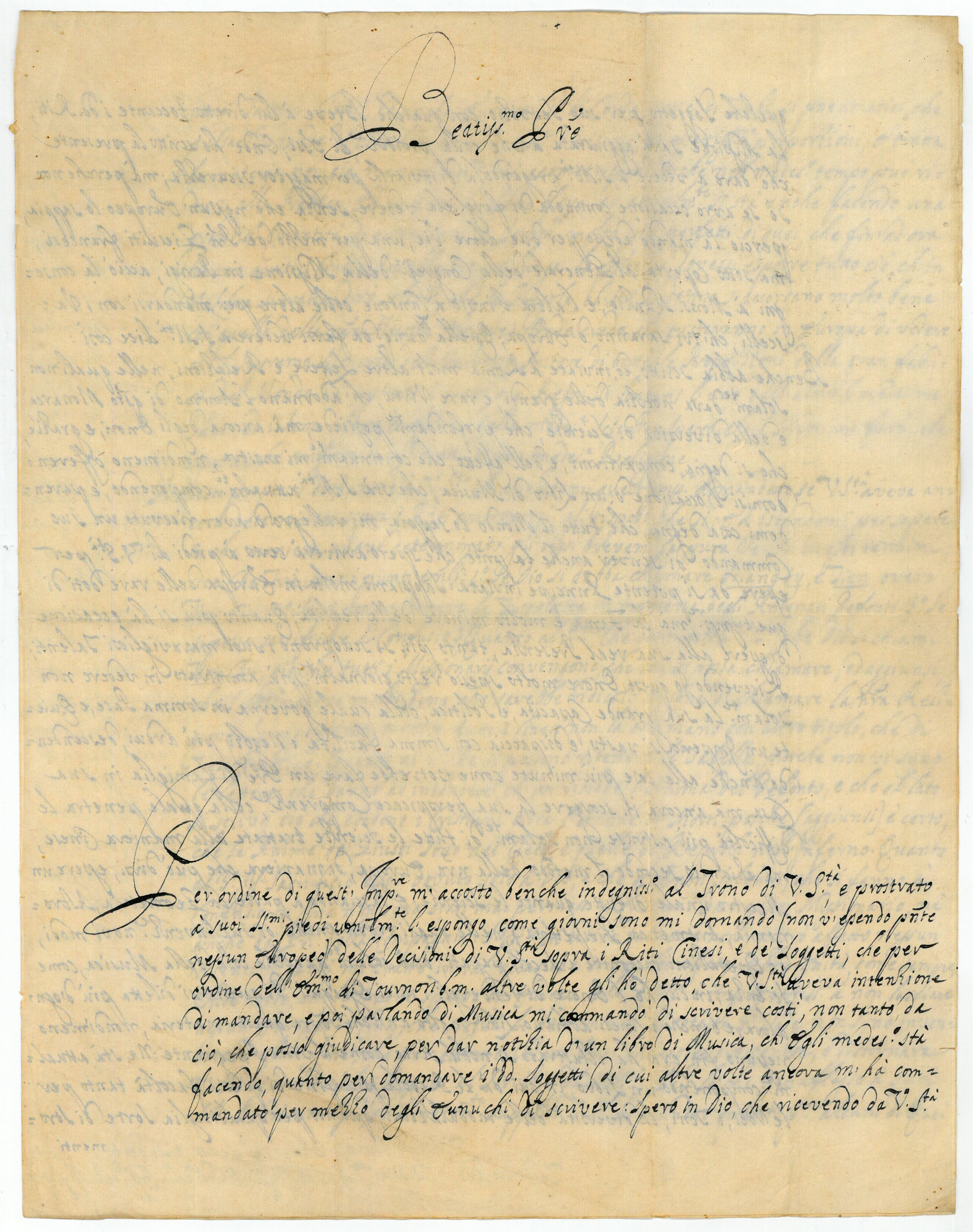

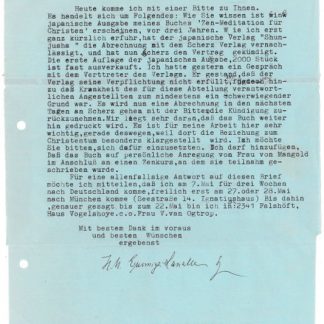

Autograph letter signed.

Folio. 4 pp. on bifolium. In Italian.

€ 12,500.00

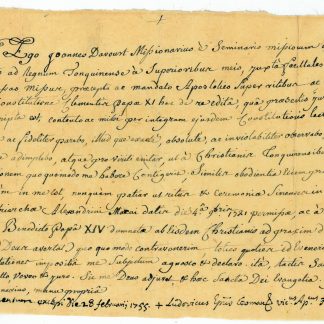

Historically important letter written from the imperial summer palace in Chengde, Hebei province, to Pope Clement XI, reporting on an audience wherein Pedrini had informed the Kangxi Emperor of the most recent Papal decisions concerning the practice of the Chinese rites. The document at hand is Pedrini's autograph fair copy; the only other known and published copy is an identical calligraphed version in the Vatican Apostolic Archive.

The Vincentian Pedrini probably knew Giovanni Francesco Albani, the later Clement XI, personally, as they both frequented the Collegio Piceno of the Casa della Missione di Monte Citorio, the Accademia dell'Arcadia, and the salon of Cardinal Ottoboni in the 1690s. In 1702, Pedrini was selected as a member of the first Papal legation to Beijing of Carlo Tommaso Maillard de Tournon, but he did not manage to join the ill-fated mission due to several long delays in his journey to China. Only in January 1710 did Pedrini reach Macau together with Matteo Ripa, where he met the gravely ill Tournon, who had been exiled from mainland China by the Emperor and placed in Portuguese custody.

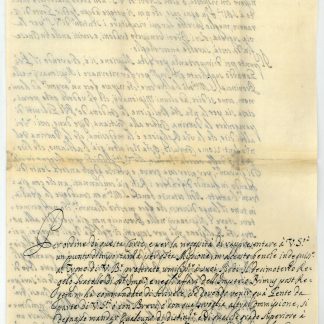

Despite the Jesuits' efforts to keep Pedrini and the other missionaries of the Propaganda Fide away from the Imperial Court, the Kangxi Emperor called him to Beijing to benefit from his knowledge of Western music. Upon his arrival in 1711, Pedrini was immediately employed as a musician and music teacher to the princes, soon gaining the Emperor's trust. At this time, the Emperor was largely unaware that the controversy about the Chinese rites persisted beyond the sorry episode with the diplomatically inept Tournon, which is mainly attributed to the influence of the Jesuits. In the October 1714 audience that is described in the letter, the Emperor questioned Pedrini about his position concerning the Chinese rites and, more importantly, news from Rome. According to testimonies by the Procurator of the Propaganda Fide missions in China, Giuseppe Cerù, Pedrini was initially hesitant to answer the Emperor for fear of negative consequences. After some encouragement, he finally broke the news of the ongoing controversy to the Emperor. A few days thereafter, Pedrini wrote the letter at hand to inform the Pope personally, apparently following the wishes of the Emperor himself. Curiously, the letter cites another letter describing the audience: Pedrini explains that he will have the cited letter authorized by the Emperor but feared subsequent censorship or alterations, as the official correspondence was controlled by the Jesuits. Indeed, the high-ranking German Jesuit Kilian Stumpf started a process of amending and changing the official letter after its authorization by the Emperor before it was finally dispatched to Rome on 9 December 1714.

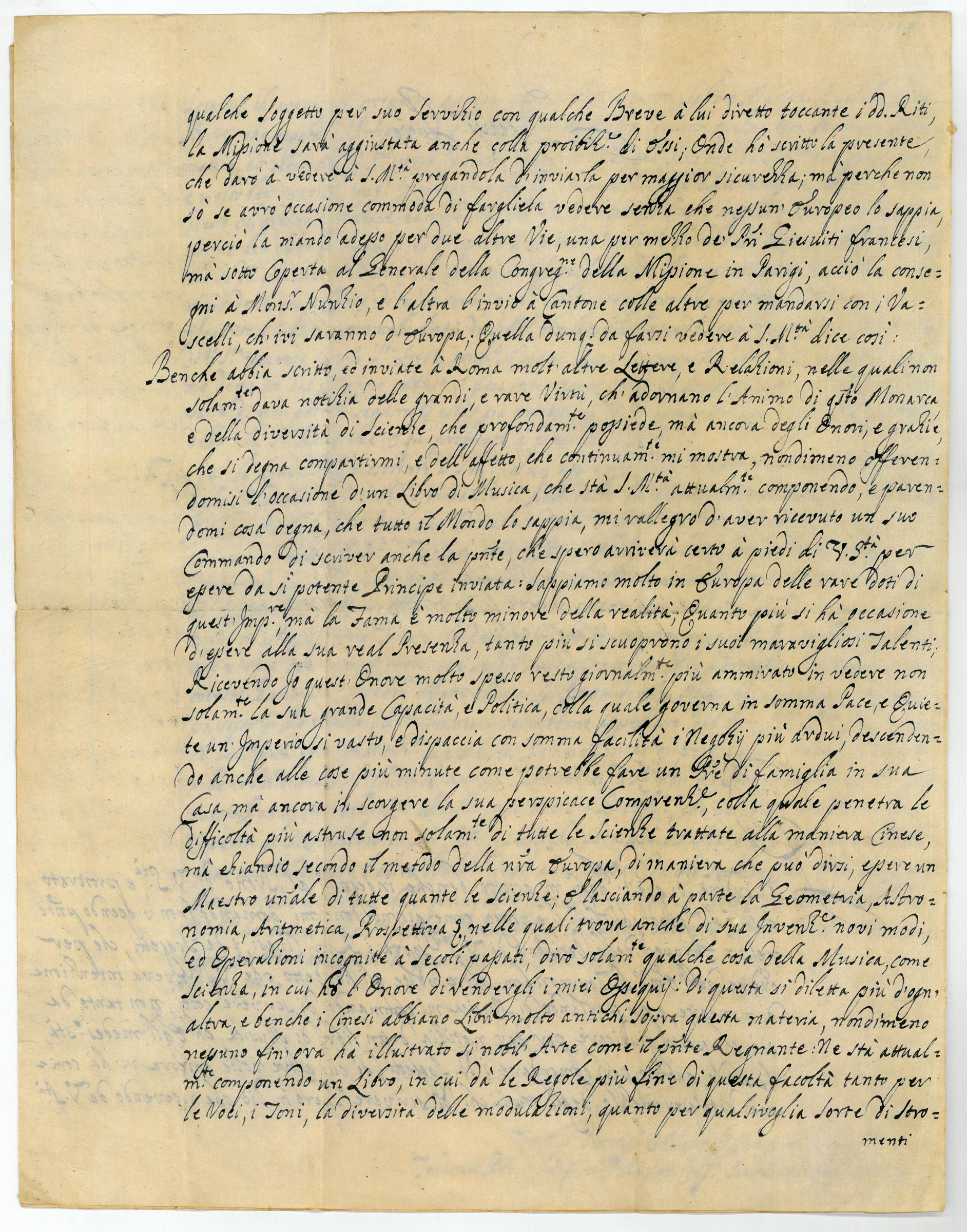

In his account of the audience, Pedrini relates that the Emperor had asked him, in the absence of any other European, about the Pope's decisions before moving on to discuss musical matters. Importantly, Pedrini stresses that he does not think a renewed Papal interdiction of the practice of the Chinese rites would compel the Emperor to impede Christian missionary work altogether, as the Jesuits argued. Concerning music, Pedrini mentions the Emperor's wish for him to complete Tomás Pereira's "Lulu Zhèngyì-Xùbian", the first treatise on Western music theory written in Chinese, which Pedrini would achieve by the end of 1714. The letter within the letter ("The one therefore to be shown to His Majesty says thus: […]") starts with a panegyric of the Emperor, praising his virtues as a politician and as the head of his family and his interest in and knowledge of Chinese and European sciences. Concerning the controversy over the Chinese rites, Pedrini sums up the three principal points of contention, together with the Papal positions on them. These were: 1) the use of the Chinese words 'Tian' (Heaven) and 'Shangdi' (Lord Above/Supreme Emperor) for the Christian God instead of or alongside the accepted term 'Tianzhu' (Lord of Heaven); 2) the continued use of tables with the inscription "site of the soul" that were part of ancestry worship; 3) the participation in the annual rites for Confucius and sacrificial offerings in this context. In an echo to Cerù's report on Pedrini's apprehensions, he recounts that the Emperor "showed no resentment at all", treating him "on the contrary [...] with much affection and goodwill, as always". This was, of course, both flattery and part of an argument allowing for the conclusion that "news spread in Europe", presumably by the Jesuits, that the Kangxi Emperor will "not allow in China any Europeans who follow the decisions of the Holy See", are a pure fabrication with "no other end than to terrorize those who wish to come" and to dissuade the Pope "from sending other subjects to the service of His Majesty".

On this note, Pedrini asks for a painter versed in perspective, a physician and surgeon, a musician, and a mathematician. It can be assumed that he was not hoping for the likes of the Jesuit lay brother and painter Giuseppe Castiglione, who at this point was already on his way to Macau. The cited official letter ends with Pedrini's hopes that the Emperor "will allow everyone to observe peacefully the decisions of His Holiness concerning our Sacred Law". In closing, he offers a short account of current affairs within the community of missionaries that points to bitter religious and political divisions, specifically mentioning attempts by the Portuguese Jesuits to bring the autonomous French Jesuit mission in China under their control. According to Pedrini, the Italian Jesuit visitor of the Superior General, Giampaolo Gozani, served as a tool of Portuguese interests. He also mentions with some bitterness that Gozani was probably "made visitor" by "merit" of spreading rumours about the Vicar Apostolic of Fujian, Charles Maigrot, M.E.P., who had a long-running conflict with Gozani and the Jesuits, as he was the first Catholic official in China to condemn and ban the practice of Chinese rites in his diocese as early as 1693.

The update from Rome certainly prepared the Emperor for things to come, particularly the 1715 bull "Ex Illa Die", condemning the practice of Chinese rites, though probably not in the way that Pedrini had hoped for. The official letter to the Pope from 9 December already included a note by the Emperor, wherein he sides with the Jesuits' position. When, also due to the persistence of Pedrini and Ripa, news of the bull reached Beijing in August 1716, the Emperor reacted immediately and demanded all missionaries at the court, including Pedrini, to sign the so-called Red Manifesto of 31 October. The manifesto stated that since there was no news of the Emperor's own envoy to Rome, the Jesuit Joseph-Antoine Provana, no credence could be given to any documents regarding the Chinese rites reaching China through unofficial channels. Provana was subsequently allowed to return to China but died en route in 1719. Thus, the Papal Legate Carlo Ambrogio Mezzabarba was sent to negotiate with the Emperor, but the mission failed, leading to an official ban of Christian missions and Pedrini's two-year imprisonment in the residence of the French Jesuits for failing to sign the so-called "Diarium Mandarinorum", an official account of the events drawn up by the French Jesuits.

In very good condition with minor browning and minimal foxing.

Teodorico Pedrini, Son mandato à Cina, à Cina vado. Lettere dalla missione, 1702-1744 (Macerata, Quodlibet, 2018), pp. 535-540.