Opera.Paris, 1799.

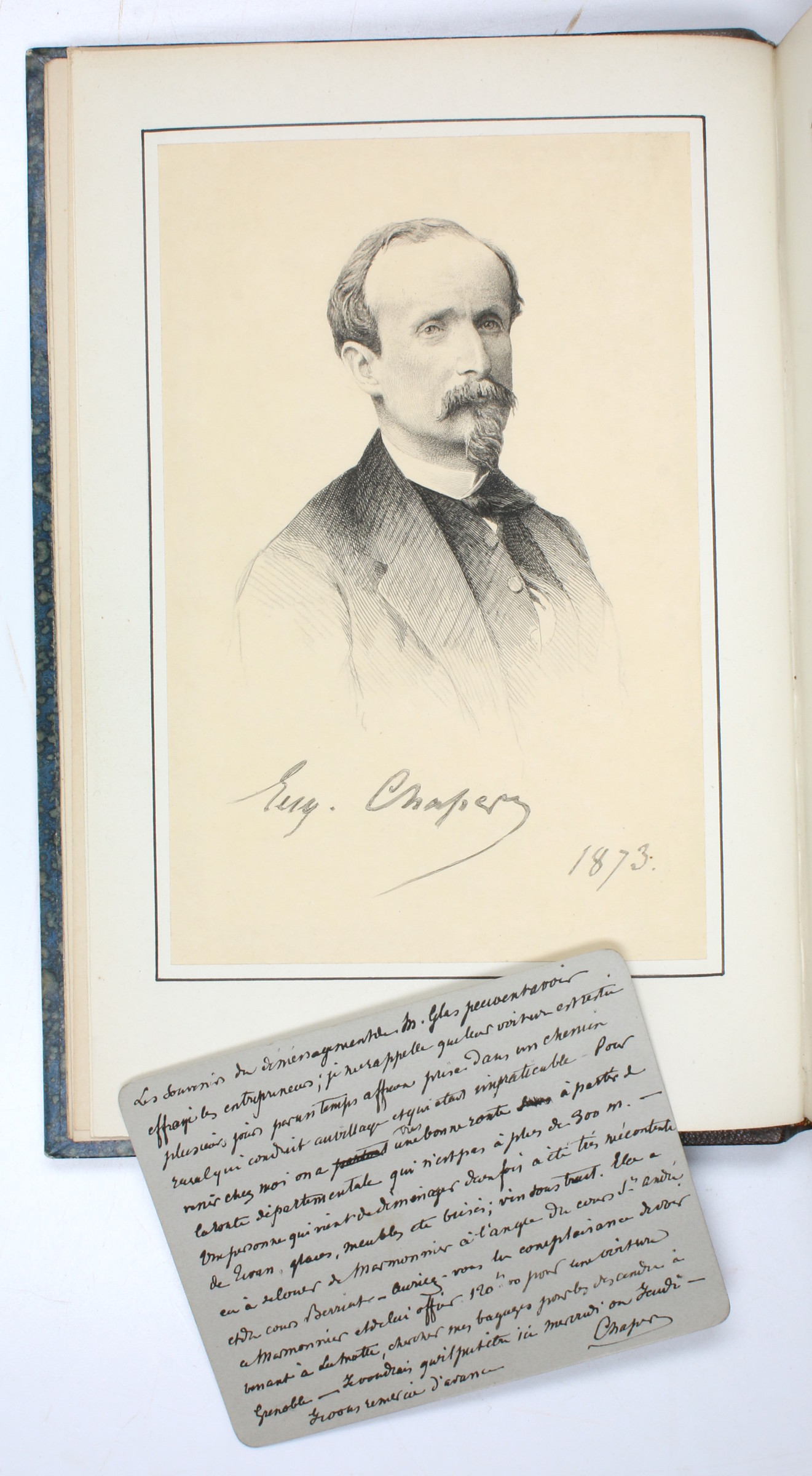

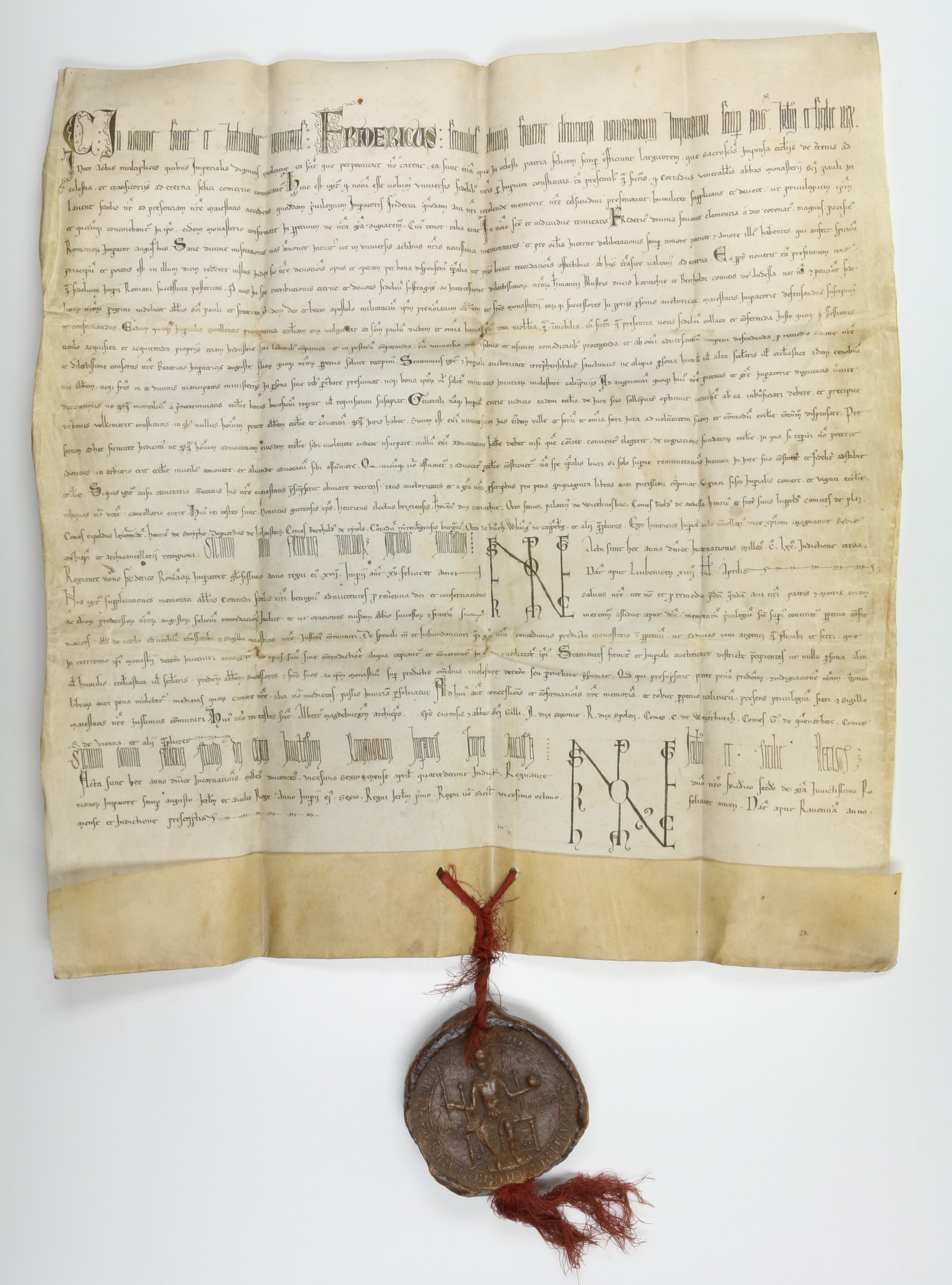

Didot's "Louvre" edition of Horace, limited to 250 copies, of which this is no. 46 (and one of 100 copies containing the engravings "avant la lettre), signed by the publisher Pierre Didot the Elder ("No. 46 quarante-sixieme sur deux cents cinquante. P. Didot, l'aine"). The elegant unsigned binding is to be attributed to the Viennese artist bookbinder G. F. Krauss (active 1791-1824), showing the distinguishing features of his production. Krauss was the most prominent German bookbinder of his day, and the Duke of Saxe-Teschen was perhaps his most important client. Martin Breslauer's catalogue 110 offered a Krauss binding for Duke Albert, signed with his stamp "G. F. Krauss, Relieur à Vienne" and obviously performed in the same style and with the duke's monogram. Another fine example, unsigned like the present one, is pictured in the catalogue of Otto Schäfer's binding collection.

Duke Albert, Maria Theresa's son-in-law and sometime governor of Hungary and then of Belgium, was a collector of the first order. His collection of graphic art forms the nucleus of Vienna's Albertina; "as a bibliophile he evinced a special taste for good typography [...] Oddly, scholarship was long at a loss to identify Albert's bookbinders. Only recently [with the discovery of Breslauer's signed binding] could it be proved that Krauss bound at least parts of Duke Albert's library" (Schäfer). Works from the Krauss bindery have passed through some of the most distinguished collections over the years. There is but a small number of books printed by Didot and Bodoni which had the chance to be bound by Krauss.

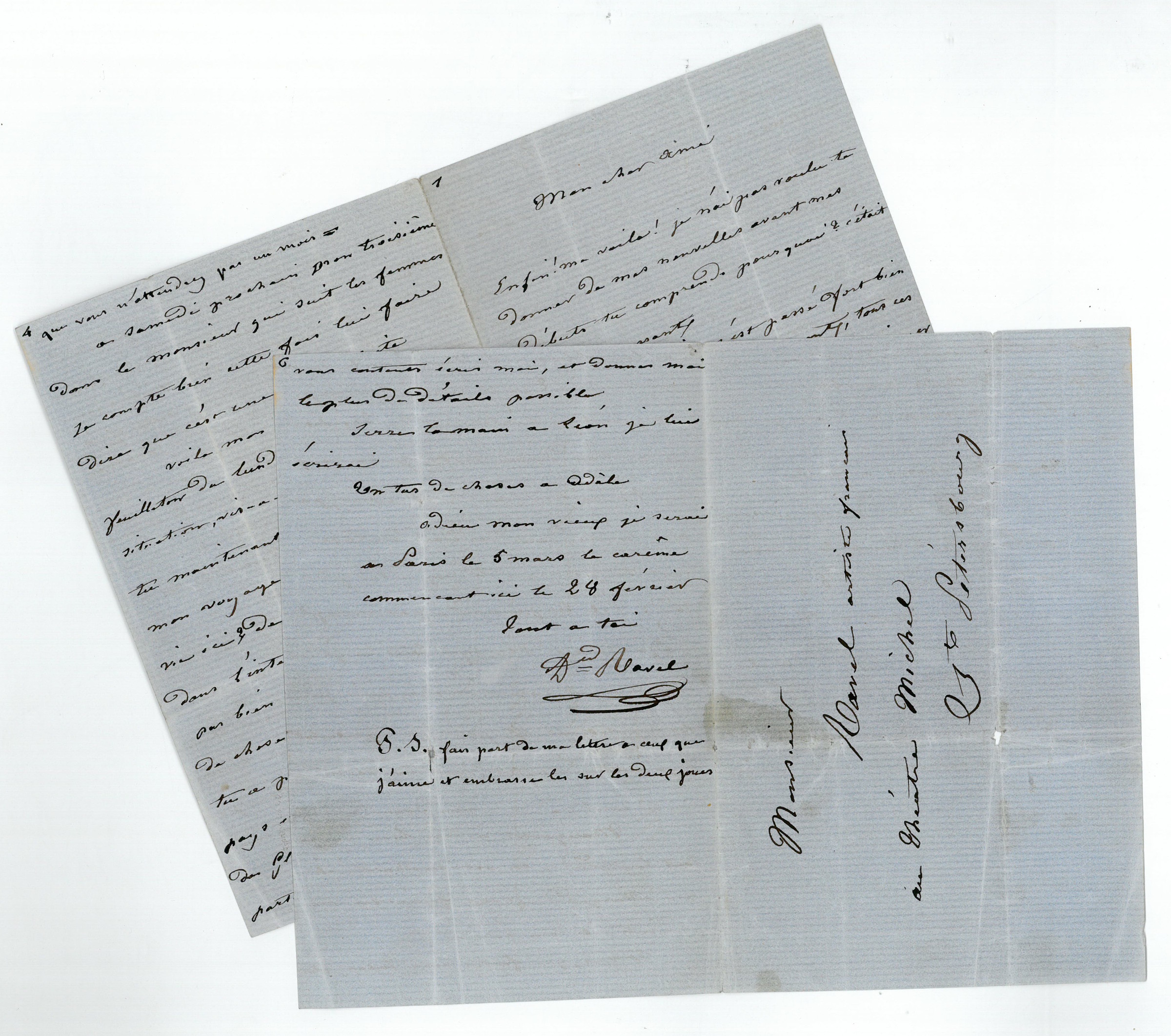

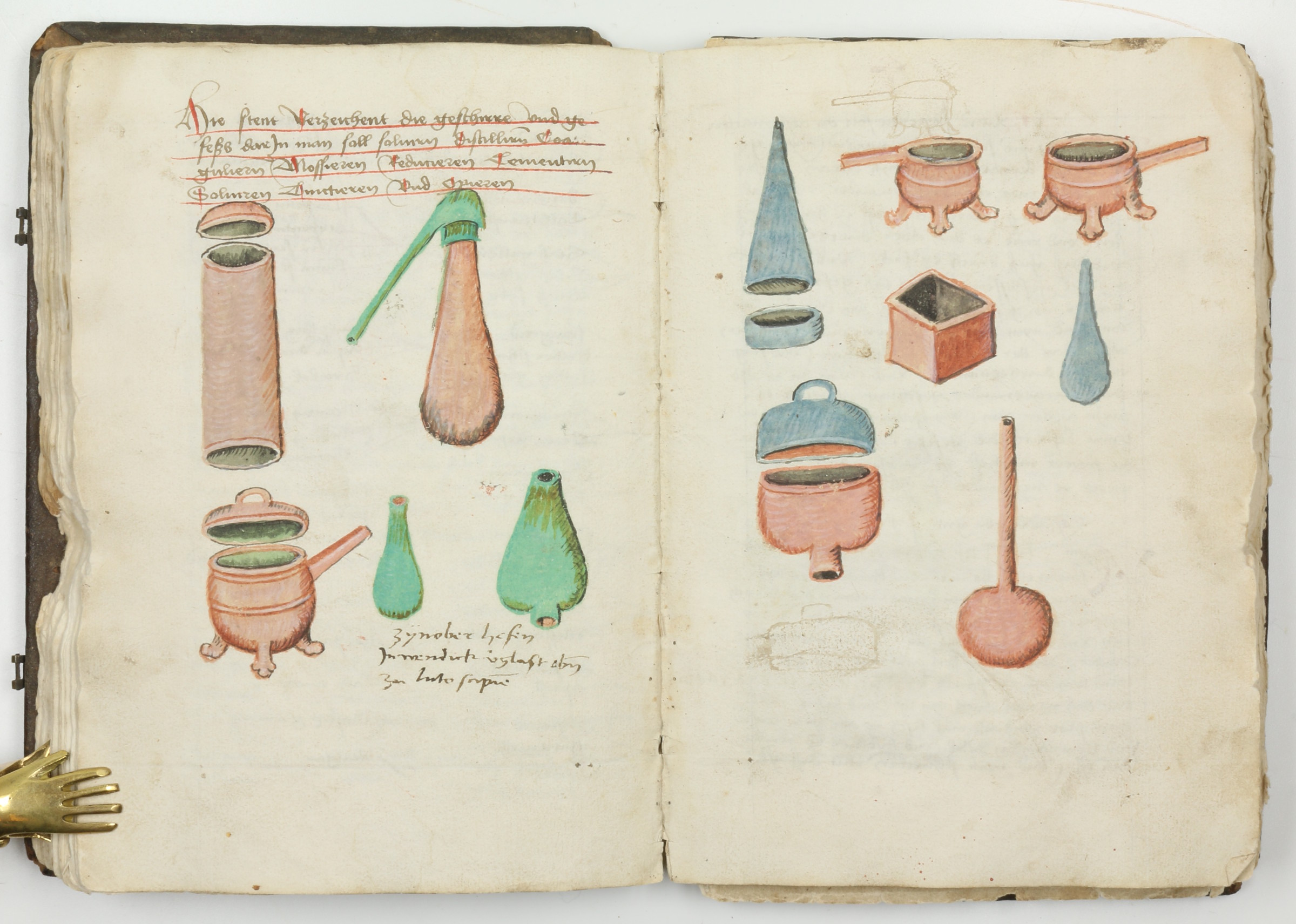

Pierre Didot (1760-1853) was a third generation member of the prominent Parisian publishing family, Didot, renowned for the immaculate quality of their books. "When Pierre Didot l'ainé chose to adopt his own fount of letter - how exquisitely does it appear in the folio Virgil of 1798, and yet more, perhaps, in the folio Horace of 1799!? These are books which never have been, and never can be, eclipsed. Yet I own that the Horace, from the enchanting vignettes of Percier, engraved by Girardais, is to my taste the preferable volume" (Dibdin). Pierre and his younger brother Firmin took over the family business in 1789. Among their first projects was a supremely luxurious suite of the works of canonical authors from antiquity and France known as the 'Louvre' editions because they were launched when the firm occupied a studio space in the Musee du Louvre. The importance of these luxury editions - printed on the highest quality paper, illustrated by the leading artists of the period in Neoclassical style, and printed in a new type face designed exclusively for these editions - cannot be overstated: "The distinction of this set of folios resides in its scale, abounding illustrations, and its consequentially exorbitant production costs. Though it was not a commercial success, these books endure as Pierre's crowning achievement among the hundreds of editions he produced in his career, and easily the most significant illustrated set of books in the period" (Metropolitan Museum of Art). Didot himself, in a letter to Talleyrand, said of his Horace, "la superiorite d'execution de cet ouvrage ... l'emporte evidemment sur celle [du] Virgile [...] La gravure des vignettes est un chef-d'oeuvre".

Some light foxing throughout; dampstains around Didot's signature as a mark of authentication. The sumptuous binding is impeccably preserved. From the collection of the New York banker Lucius Wilmerding (1880-1949), trustee of the NY Public Library, vice-president of the American Library in Paris, and president of the Grolier Club, with his bookplate to the front pastedown.